The Louvre Abu Dhabi is up there with Ronchamp and the Kimbell in the way it manipulates light. Phil Coffey draws lesson for the whole profession

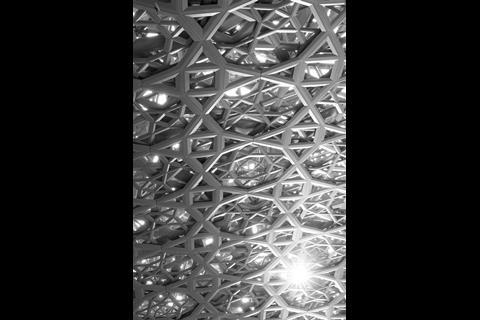

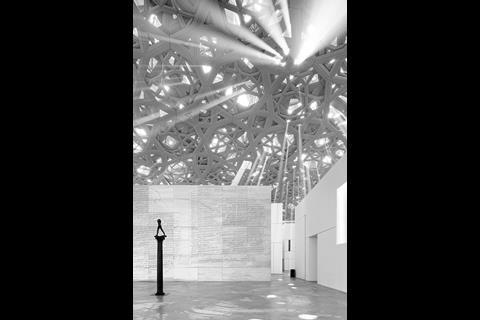

The Louvre in Abu Dhabi is a masterpiece. The route, the experience, the mashrabiya roof – and the light, OMG, the light. On return to the UK from a two-day photographic visit in this space that is all about the roof, a colleague asked, “What’s it made of?” I must admit I was at a loss.

Roofs are where architecture has often expressed its sustainability “credentials”, be it through wind turbines, photovoltaic cells, chimneys for air or green planted landscapes. Obvious signals of energy production, ecosystems and natural ventilation. It’s one way we can express architecture’s relationship with the environment, but in a more and more commercial world these opportunities are scarce, require a cost lifecycle analysis that it seems can rarely be afforded and the whole adventure requires a client open to environmental ostentation.

A more modest way to meet the growing demand for the so called “tree hugging” architectural solution is to use materials and create comfort levels that check boxes. We are now mired in environmental jargon, standards and endless pages of marks for bin stores. Excellent, Outstanding, Breeam, Leed are all examples of architects losing ground within our industry by turning the qualitative to the quantitative. It’s not how it look or how it feels, it’s how it performs. Building science writ large.

So, is sustainability as a driving architectural force dead? Maybe, but perhaps there’s a wider question here for us as a profession. The big shifts in modern architecture have occurred due to social change or material change. A warming planet is the issue of our time, and surely it is incumbent on contemporary architects to connect people more viscerally to their environment.

In 1985 in his lecture at the Welsh School of Architecture, a school renowned for its early adoption of environmental building science, Tadao Ando pointed to a small “slice of the sun” on the covered route to the Mount Rokko chapel that happened to mark the entrance and observed: “So real you feel you could kneel down and pick it up.”

The manipulation of light is the profound way that architects can capture a little piece of the cosmos for users and make it real. Great architects quite literally make space for architecture. Fine works such as the Kimbell, Can Lis, Saynatsallo, Kandalama and Ronchamp all manipulate light to connect users to place and the new Louvre is up there with them. Differing building types that manipulate light through roofs and walls.

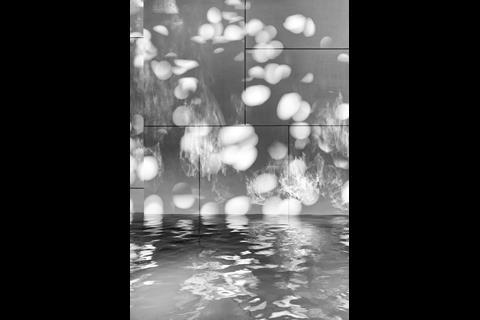

As people leave the final exit from the Louvre gallery complex, their delight in dancing and moving from pool of light to pool of light under the multi-layered dome is enchanting. Smiles abound, with people from all walks of life talking to one another about the beauty of it all. Architecture at its best touches every single one of us and, by being touched by nature, might we all care a little more for it?

I have now read the book, studied the section and seen the YouTube video of construction of the roof and I’m duly impressed. But the real beauty, the real experience, the real connection doesn’t lie in the fabric, it lies in the way light penetrates the space. When interviewed, Jean Nouvel doesn’t talk about the material, the seemingly effortless structure. He poetically describes the Louvre as a “rain of light”. He sells the effect, not the cause.

So, yes, let’s seek overt expression, let’s work with the number crunchers to save energy and create comfort, but let’s also remember that architecture in and of itself can be environmental by connecting people to place through the poetry of light and creating space that connects us to nature.

To paraphrase a well-known saying, when we next sit down with our clients to talk environment, let’s remember to, “Sell holes. Not roofs.”

2 Readers' comments