Can the new ‘grey belt’ concept provide a pathway to sustainable housing without sacrificing the green belt, asks Jerry Tate

Labour was the only political party to be honest about what needs to be done to deliver 1.5 million houses over the next five years – some of them will need to be built on the green belt. As a practice with a particular specialism in sensitive landscape settings, we have considerable experience on green belt sites. From this, I believe the concept of a ‘grey belt’ is an opportunity to ensure the absolute best practice in housing design, which I believe means making all developments follow Regenerative Design principles to gain consent.

The new concept of the ‘grey belt’ is set out in the draft NPPF, released by the Government on 30th July 2024 for consultation. While the exact definition of the ‘grey belt’ is not precisely set down, it essentially encompasses poorly performing parts of the green belt (not necessarily previously developed land). This is a useful definition for an area that could potentially be released from the green belt without detrimental consequences to the local environment. The draft NPPF is very clear about what a scheme must deliver to be released from the green belt:

- Deliver 50% affordable housing (subject to viability, which is defined in a reasonably complex way).

- Contribute necessary improvements to local or national infrastructure.

- Provide new or improved green spaces that are accessible to the public and new residents.

While these are commendable targets, I think there is an opportunity to supplement or balance them with requirements to deliver truly low-carbon and regenerative developments and communities (the desire for which is set out separately later in the document). Essentially, I believe the targets could be refined to ensure that the ‘grey belt’, if developed, delivers multiple positive outcomes for both people and the planet.

Until now, if you wanted to develop in the green belt, you either needed to demonstrate that what you wanted to do was appropriate (some leisure uses fit this category), or that the site had Special Circumstances (this cannot just be about delivering homes). In our experience, a successful strategy for gaining consent in the green belt involved the following:

- Green belt assessment – Demonstrate that the site is not performing well as a piece of green belt. This often means that although it is technically in the green belt, the site has a critical issue that makes it more akin to a ‘Brownfield’ piece of land. Examples we have worked with include redundant water treatment works or old oil storage depots.

- Design – Create a design that delivers multiple and exceptional benefits, such as a dramatic improvement in biodiversity; creating key sustainable transport connections (for example, a cycle or pedestrian link from an existing community to a train station); repairing an issue, such as removing a dilapidated structure that should not be there; delivering a unique or rare natural habitat and facilitating public access to it; or indeed delivering a higher percentage of affordable housing than is usually required.

- Landscape and Visual Impact – While this is not technically the same as the ‘Openness’ test for the green belt, if what you are proposing will have a positive effect on visual impact, the chances of gaining consent are significantly improved.

- Special Circumstances – Use the above to generate a Special Circumstances argument. This can be a ‘layered’ approach, demonstrating multiple benefits the scheme can deliver, or more likely, an exceptional and unique combination of benefits.

As you can see, the critical first step is acceptance that the site is a poorly performing part of the green belt, and this is the very definition of the ‘grey belt’ concept. A change in legislation that guarantees the recognition of sites that are green belt ‘in name only’ would be a significant step in unlocking many potential development plots across the UK. However, in our experience, the three steps following this first one can deliver exceptional housing schemes that demonstrate what best development practice can truly look like in the UK.

While I agree that we should set a very high bar for developing sites on the green belt, I believe that by broadening and balancing the requirements of what the site must deliver, we could create a new generation of housing based on Regenerative Design principles that would offer multiple positive benefits for energy and carbon, nature and biodiversity, as well as people and communities. For example, by following the above strategy, we gained detailed planning consent in 2021 for a project called Esholt Positive Living, on the green belt between Bradford and Leeds. Working for Yorkshire Water and Keyland Developments, we developed a ‘whole site’ approach that sought to replace a redundant water treatment plant with new homes and commercial development.

The key to unlocking the site was taking a holistic approach across the wider site (totalling 73 hectares), going beyond the development red line boundary to create a new country park. This allowed the residents of the existing Esholt village to walk and cycle to Apperley Bridge Station. Through careful analysis of the available natural and man-made resources on the site, as well as potential improvements in sustainable and natural connectivity, we demonstrated to Bradford Council that the site could deliver an example of Regenerative Design that would substantially improve the quality and environment of the local area, as well as deliver much-needed market and affordable housing. We also gained substantial local community support.

I am sure some will question why we need to build on the green belt at all, but recent research by Lichfields shows that there is simply not enough brownfield land to deliver 1.5 million homes over the next five years. Given this, I think we should embrace the concept of the ‘grey belt’. With the value this will create for landowners, we have a real opportunity to embrace Regenerative Design principles. This would not only deliver homes but also restore our relationship with the natural world. Let’s turn the ‘grey belt’ green!

>> Also read: From green to grey: How the grey belt could steer development towards the wrong places

>> Also read: How suburban intensification could hold the key to delivering Labour’s 1.5m homes target

Postscript

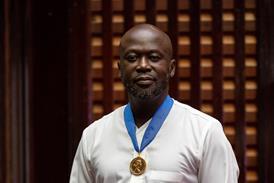

Jerry Tate is director of Tate+Co Architects

1 Readers' comment