The practice that Michael and Patty Hopkins founded has produced some of the best British architecture of the last half century, writes Ben Flatman

Must contemporary architecture, by definition, reject the past and prioritise technical innovation at the expense of history and tradition? For a growing generation of architects, such binary choices no longer exist.

After the fraught style wars of the 1980s and the overbearing “iconic” starchitecture that dominated the turn of the millennium, British architecture has mellowed. Architectural debates are perhaps less polarised and explosively contentious than they once were, but the actual architecture is probably better for it. There’s a pluralism now that allows for a more nuanced approach to the past.

Michael Hopkins’ significance as an architect arguably lies in the leading role that he played in breaking through those tired old debates about modernity versus tradition. Through the work produced by the practice he founded with his wife, Patty Hopkins, we can see how British architecture evolved during a period of massive economic and societal change.

The beauty of Hopkins’ architecture was that it emphatically refused to accept that there were clear boundaries between the past and present. Instead, it reasserted the age-old truth that the best contemporary architecture is very often rooted in a profound appreciation for the past.

This might not seem like an obvious conclusion to draw from an architect who is seen as having been at the forefront of the British high-tech movement. One of Michael and Patty Hopkins’ first projects was their own house, which clearly sits in that high-tech tradition.

But as their practice grew in size and stature, so its architectural language evolved. The much-copied Mound Stand at Lords Cricket Ground was notable for the way in which it managed to popularise modern architecture in the context of a quintessentially conservative institution.

Its playful canopies, with their clear allusions to the temporary marquees of a village cricket match, signalled a more relaxed approach to form. Retention and reuse of the brick arches from the original stand also pointed towards the practice’s future interest in masonry structures and its work in sensitive heritage contexts.

The practice also helped stretch the boundaries of the modernist aesthetic to embrace a growing fascination with the material warmth and versatility of timber. High-tech began to merge with brick, wood and stone to produce a new hybrid architecture.

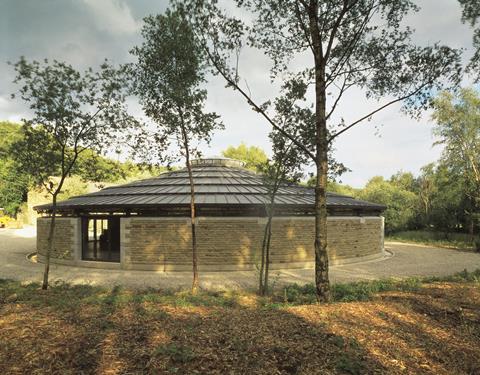

The David Mellor factory in Derbyshire is a seminal work of late twentieth-century British architecture, and one of the most assured and beautiful small buildings of the 1980s. Built on the footprint of an old gas holder, it displays a sensitivity towards place and materials that came to represent much of the practice’s best work.

The floating, column-free roof structure betrays the practice’s origins, but the melding of high-tech’s engineering fetish, with the grounded monumentality of the building’s simple masonry base underlines the new direction in which Michael and Patty Hopkins were moving.

The practice’s Bracken House in the City of London is for many a touchstone example of how to insert new structures within an existing fabric. Hopkins’ central addition to the listed former FT building manages to complement the original Albert Richardson-designed office blocks on either side, while retaining a striking modernity that has not dated with time.

The design picks up on Richardson’s own references to Palazzo Carignano in Turin. And it highlights the apparent ease with which the practice was able to navigate the pitfalls of postmodernism, while still making overt references to a seventeenth century palazzo.

Glyndebourne Opera House followed in 1994, by which point the practice had become almost the architect of choice for prestige cultural and official commissions. Glyndebourne’s seductive timber-lined auditorium and brick arcades showed again that contemporary architecture could be at once modern, sensitive to context, and hugely popular.

The Queen’s Building at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, is another gem that works almost like a miniature-Glyndebourne.

It was the practice’s sensibility, as much as the formal expression of the architecture, that was to have such a significant influence on so many future architects. By tapping into rich seems of historical precedent, and blurring the lines between what constitutes modernity and tradition, Michael and Patty Hopkins fed a growing appetite for a more nuanced approach to history and design.

1999’s Portcullis House was widely seen as a misstep. But with its natural ventilation strategy and lushly vegetated glazed courtyard, the building is not only successful as an office building, but also an early adopter of important new priorities around sustainability.

Portcullis House seeks to echo and complement the nearby Norman Shaw Buildings. It is not hard to see it long outliving many other late twentieth century additions to Whitehall.

>> Also read: Tributes paid to Michael Hopkins

>> Also read: Sir Michael Hopkins dies aged 88

And beneath it of course sits the sublime, piranesian marvel that is Westminster underground station. Nothing else on the Jubilee Line Extension or the recently completed Elizabeth Line really comes close in terms of sheer jaw-dropping drama.

The list of Hopkins buildings that continue to act as essential reference points for contemporary architects is immense and extends far beyond the few examples that I have mentioned here.

Any discussion of Michael Hopkins’ contribution to architecture must of course include recognition that Hopkins Architects was co-founded by, and run in partnership with, Patty Hopkins. Her own contribution to the practice’s work has all too often been ignored and on occasion literally airbrushed out of the story. Their work together – alongside their other partners and staff – is truly a remarkable shared achievement.

2 Readers' comments