Unless the government underpins the Oxford-Cambridge corridor with a strong implementing framework, all the good ideas will come to naught, warns Hank Dittmar

Last week saw the announcement of the four-strong shortlist for the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford Corridor design competition, sponsored by the National Infrastructure Commission. The commission will be publishing a report this autumn outlining a strategy for the corridor, which will draw from the competition submittals alongside other inputs. They envision £100 million of rail funding to deliver a western phase by 2024, improvements in road links and a joined-up local/national housing and infrastructure strategy.

For a country which arguably invented public transport-orientated development with the Metroland growth of London, much recent development around public transport has been disappointing. The Docklands have not seen housing and jobs as integrated, Ebbsfleet has prioritised parking, and most big station projects have been shopping-oriented. King’s Cross is an exception. The Cambridge-Oxford project is of a regional scale, and links jobs centres with attractive residential areas, holding promise.

The shortlist includes two teams led by planning firms: Tibbalds and Barton Willmore and two led by architects: Mae and Fletcher Priest. They will each receive £10,000 to develop designs for development typologies for the corridor. While there are some interesting concepts presented, I fear this competition is mostly vapourware.

Barton Willmore’s “CAMKoX Innovation Hive” postulates an organic growth model featuring a pioneer phase with public realm, infrastructure and pop-ups delivered early, later consolidation with autonomous vehicles and pop-ups getting Michelin stars, and a Community Land Trust holding back land for later development. National parks, local food strategies, renewable energy and geodesic domes and other buzz words dot the landscape in its build-out phase.

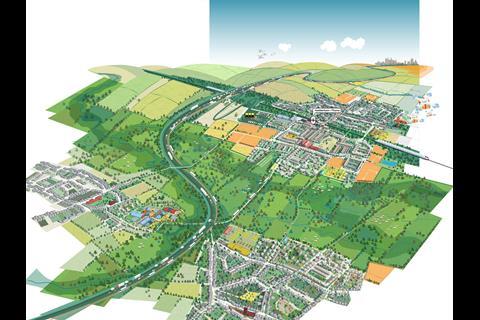

The Fletcher Priest Architects submission moves quickly from a strategic corridor diagram to a test site at Haddenham and Thame, looking beyond the larger cities to test the ideas of town and village expansion around a new station. The proposal for a spectrum from urban extension to new settlement is embedded within a landscape strategy that manages water and protects habitat corridors.

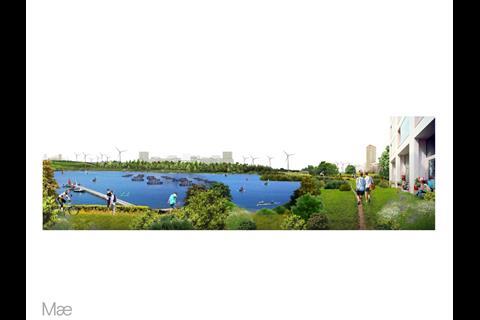

Mae’s team directly answers the brief with a coherent plan for connectivity and overview of 10 development typologies. The submission develops one of these typologies called A New Living Campus, identifying locations for clusters of up to 50,000 people in a dozen locations on the corridor. Mae proposes both a physical planning proposition and a design concept appropriate to the corridor.

Tibbalds proposes VeloCity, a “modern day picturesque” strategy, with development typologies drawn from village patterns — called the field, the farm, the manor and the shed and describing block types. They propose a bicycle-oriented movement network and envision beginning with a pilot project. Tibbalds also sprinkles buzzwords on to their map, including fibre, productive landscape and light-touch living.

Mae’s proposal is the most realised of the lot, but all four suffer from a fault not their own but endemic to the competition: the unrealisable gap between vision and the reality of how this will work on the ground without a strong hand from government. If the project is delivered true to form, the rail and road infrastructure will be followed by speculative proposals from house builders, who will use planners like Barton Willmore and Tibbalds to paint pretty word pictures. Land owners will hold out for best price, housing numbers will be emphasised, and a lot of executive homes will be built on town outskirts with two-bedroom flats near the stations.

Perhaps the infrastructure commission will address this unhappy reality, but its talk so far has been of local partnerships. One useful suggestion in its interim report is to establish Urban Development Corporations in the corridor. An Oxford-Cambridge Corridor Development Corporation could be empowered to purchase sites at close to agricultural land values, to work with local authorities and parishes to plan urban extensions and new settlements, provide infrastructure, and sell serviced parcels complete with design briefs. Doing this in small plots can enable community builders, SMEs and local enterprise and locally responsive designs. Underneath such a strong implementing framework, local communities could develop as suggested by the teams as innovation hives, picturesque VeloCities, middle sites or living campus communities.

There is a tendency to use these kind of design competitions to generate enthusiasm, without connecting them to implementation. I fear that is the case with this one, unless the winning design is given a pilot site overseen by an urban development corporation. It’s a pity, for there were some good ideas here, especially in the Mae and Fletcher Priest submissions.

3 Readers' comments