New York museum seeks to put region’s architecture in a post-colonialist context, writes Ben Flatman

I have mixed feelings about MoMA and its relationship to architecture. Its first head of architecture, the former Nazi-sympathiser Philip Johnson, famously curated the Modern Architecture exhibition in 1932 that helped to distil architectural modernism into the “international style”.

Johnson arguably did more than anyone else to turn what had been a diffuse and varied movement into something far more sterile and commodifiable. Smoothing over regional diversity and stylistic heterogeneity, he oversaw the development of the dominant strain of modernist architecture to the point where it became the house style of globalised corporate capitalism.

The curation of MoMA’s current show, The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985, has echoes of that earlier 1932 exhibition. A very conventionally presented mix of archive and newly commissioned photographs, alongside drawings and models, seeks to highlight how second-generation modernist architects in early post-colonial south Asia grappled with the opportunities and inherent limitations of modernism in the building of new nations, cities and political identities.

At the heart of the exhibition is the on-going debate around what modernism symbolised in the early post-colonialist context. Earlier critiques have focused on the way in which the adoption of architectural modernism – often rather simplistically seen as a western cultural imposition – simply represented a continuation of colonial constructs and westernised norms.

More recently, scholars have sought to highlight the agency with which post-colonial artists and architects wielded modernism – turning it to their own ends to convey new meaning and relevance to specifically south Asian places and contexts.

As much as I admire the UK’s role in supporting cultural relations globally, there was always a slight whiff

of neo-colonialism emanating from the work that I was engaged in

It is a fascinating debate for me personally, not least because I have spent the past decade working for a leading UK cultural organisation on a range of projects across south Asia. I have helped to build libraries in Karachi and Lahore and teaching centres in Dhaka and Jaffna, working with some of the region’s leading contemporary architects.

And, as much as I admire the UK’s role in supporting cultural relations globally, there was always a slight whiff of neo-colonialism emanating from the work that I was engaged in. Underlying Britain’s international promotion of its universities and of the English language, there was an abiding sense that (at least in part), the purpose was to perpetuate the old colonial power’s status and influence in places where those historical ties were becoming ever weaker.

The MoMA exhibition highlights the way in which modernism symbolised a break from British rule. It thoroughly rejects the suggestion that south Asians were simply the naive devotees of Corbusier and Kahn. It emphasises not only the way in which south Asian architects themselves made modernism their own, but also the uniquely localised ways in which contractors and labourers adapted to – and became highly adept at – new forms of construction.

The case is made that, far from being an alien import, modernism was an idiom through which south Asia’s architects and states explored their own newfound freedoms and sense of identity. The exhibition might have also made more of existing south Asian modernist movements in literature and art, notably in 19th and early 20th-century Bengal. In other words, architectural modernism was not something done to south Asians but rather a language that was enthusiastically embraced and grounded in the region itself.

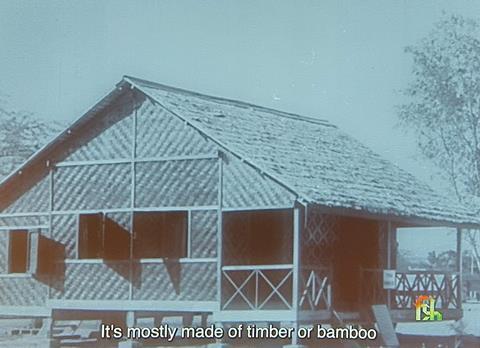

The exhibition features Modest Homes, a 1954 film about that year’s international exhibition on low-cost housing in Delhi. Produced by the films division of the Indian government, it has a British voice-over and the same air of forced joviality as many British government documentaries of the time.

The Delhi exhibition required all houses to cost no more than 5,000 rupees. Undercutting ideas that modernism has only belatedly identified the need for sustainable housing and climatic adaptation, many of the houses featured solar shading, natural ventilation and even extensive use of renewable materials, such as bamboo. Yasmin Lari, whose early modernist work appears in the exhibition, suddenly appears less of an ecological trailblazer and more the heir to a much longer tradition.

The MoMA exhibition cuts off in 1985, identified as the point when modernism’s largely unfulfilled utopian promise came under increasing attack from critiques of neo-colonialism and new expressions of cultural identity and difference. These are of course debates that continue to permeate architecture and wider culture to the present day.

Appropriately, the exhibition highlights how, from an early stage, many south Asian architects were working to rediscover some of modernism’s regional specificity that Johnson had sought to erase. Most notably, Geoffrey Bawa mixed modernism, the vernacular and climatically appropriate adaptations to create a specifically Sri Lankan architecture that has since had a massive impact on generations of architects across Asia.

Despite India, Pakistan and Bangladesh all once having been part of British India, south Asia is today one of the least economically integrated regions in the world. And yet it is evident that many of the same debates around the legacy of architectural modernism have been cutting across borders for decades. Once rejected, modernism has now been rediscovered and widely reinterpreted across the region.

It is also wonderful to see the work of Bangladeshi modernist pioneer Muzharul Islam given such prominence in the exhibition, both for his Dhaka College of Arts and Crafts and Chittagong University. Islam’s work is now widely celebrated in Bangladesh and has been a huge influence on another younger generation of architects.

With his extensive use of brick, and interest in climatically appropriate design, his legacy is clearly evident in the work of the renowned Bangladeshi architects Marina Tabassum and Kashef Chowdhury. In the work of Tabassum and Chowdhury we see the clearest evidence that modernism was always immeasurably more than some colonial hangover.

Perhaps it is appropriate then that it is in Bangladesh, the youngest of south Asia’s post-colonial states, that the exploration of architectural modernism as an expression of independence and identity still feels most relevant.

Postscript

The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 runs until 2 July at MoMA, New York

No comments yet