Bringing life back to the most challenging sites requires hard work, inspiration and a leap of faith, writes Joe Holyoak

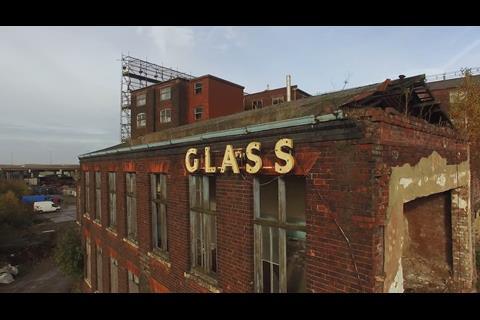

If you travel on the West Coast Mainline from Birmingham towards Wolverhampton, you are moving through an historic industrial corridor shared with Thomas Telford’s 1827 New Main Line canal. At Smethwick Galton Bridge station you may get a glimpse of Telford’s 1829 iron bridge over the canal, the biggest single-span bridge in the world when it was built. A little further on, also on the right-hand side, you will see across the canal a number of dilapidated 19th century brick buildings. One of them has the letters of the word GLASS still precariously attached to its parapet.

This is the clue that these are the surviving buildings of Chance Brothers Glass Works, once one of the biggest and most important glass manufactories in the world. But now the site is three hectares of dereliction, with only one of its eight buildings even remotely usable. The site has been nominated for inclusion in the Victorian Society’s annual list of Top Ten Endangered Buildings.

Robert Lucas Chance started the business on this site in Smethwick in 1824, as Telford’s canal, which forms its southern boundary, was being built. James Brindley’s Old Main Line canal, at a higher level, forms the northern boundary.

Production of glass continued until 1981, after which the site became unoccupied and increasingly derelict. Chance Brothers supplied 300,000 pieces of sheet glass for the 1851 Crystal Palace, shipping it to London by canal. From 1851 onwards, the firm was a pioneer in the design and manufacture of rotating lighthouse optics, enormous constructions composed of multiple Fresnel lenses, weighing several tons. Many are still in use today in hundreds of lighthouses around the world.

The Chance Brothers site contains eight buildings, all listed at Grade II. Two bridges across the canal, which connected to another part of the Chance Brothers site, are also listed at Grade II. Underneath the buildings is a network of furnaces, flues and tunnels, which is a Scheduled Monument.

The freehold of most of the site is now owned by the Chance Heritage Trust, which includes a member of the Chance family, and which was formed to find a new future for the derelict site. Part of it is on a long leasehold to another occupant. Another part is owned by a private business which bought it after Pilkington had taken over Chance Brothers in the 1950s.

A major liability is that in the 1970s, the M5 motorway was built on a viaduct above Brindley’s canal. As a result, the Chance Brothers site is subjected to high levels of both traffic noise and air pollution. The name of Chance is much celebrated locally, and there is great local pride in the firm’s history, with many older residents having worked there.

But Sandwell, in whose metropolitan borough the site is located, is not an encouraging place in which to locate new development - particularly in this unpromising corner of Smethwick. So historical importance, physical dereliction, site planning, heritage restrictions, environmental hazards and development opportunity: all these factors combine to form a complicated challenge. What can happen?

I have an interest to declare here, as from 2015 onwards I was a consultant to the Chance Heritage Trust, working on feasibility studies and masterplans for the development of the site. This role has now been handed over to the architects Bryant Priest Newman. They have the difficult task of resolving all these conflicting factors and coming up with an answer.

A major uncertainty is the feasibility of residential use. Sandwell planning authority is questioning whether the site is suitable for residential development, because of the noise and pollution and the surrounding industry. The West Midlands Combined Authority, on the other hand, is keen on the idea of high-density housing.

In any case, Historic England wants a detailed study of the protected underground assets to be made before anything is decided, and will not endorse any development proposal that risks damaging these assets. There is currently no funding available to the trust to enable this study.

Bryant Priest Newman have produced a masterplan for the development of the site. It proposes bringing all the listed buildings back into use, including the rebuilding of those canalside buildings that have already fallen into ruin, and adding new buildings. They will avoid the underground workings in the Scheduled Monument, and indeed the architects propose bringing some underground spaces into use.

One of Chance’s three canal arms from Brindley’s canal will be opened up again. The proposed residential element is 327 dwellings: partly in the converted canalside buildings, partly in new buildings.

The planning authority, Historic England, and those agencies who will fund and build the dwellings, as well as those customers who will invest their money in choosing to live there: all will have to be persuaded that an unattractive – indeed, quite unpleasant – site, can be transformed, by imaginative and ingenious design, into an attractive place for people to live and work in. I believe that it can.

I remember visiting Castlefields in Manchester during Urban Splash’s design competition for what would become their first newbuild residential development, Timber Wharf. The canalside site for that development was an unpleasant place – possibly a worse place than the site in Smethwick - and I recall having strong doubts that it could be made habitable. But it was, and so can the Chance Brothers site. But it is going to be difficult to get all parties to agree on a solution to make it so.

>> Also read: How the creative reuse of ordinary buildings is revolutionising approaches to regeneration

Postscript

Joe Holyoak is an architect and urban designer practising in Birmingham

No comments yet