Samuel Hughes explores the key elements of successful new towns through history and how these lessons might inform the new government’s housing strategy

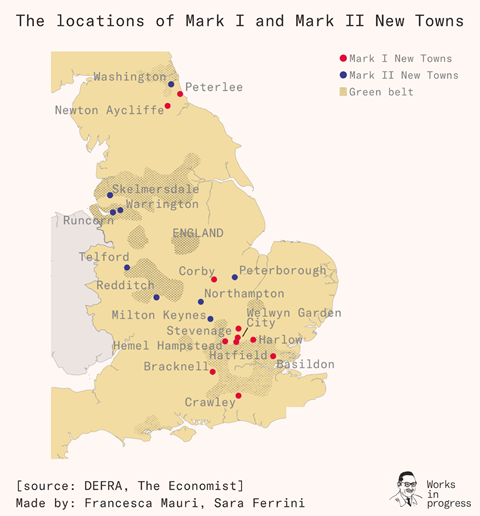

Debates about housing policy in Britain tend to go in predictable circles, with the participants repetitively invoking a small range of examples. In the case of new towns, almost the only reference points are the postwar New Towns like Stevenage, Telford and Milton Keynes, and people’s views on new towns generally tend to be determined by their feelings about these. The postwar New Towns are indeed fascinating projects, and deserve careful study.

But planned new towns in Britain have a much longer history. Reviewing that history yields some useful hints about what might make new towns work today. Those with a hardline stance against all new towns should consider the many successful examples.

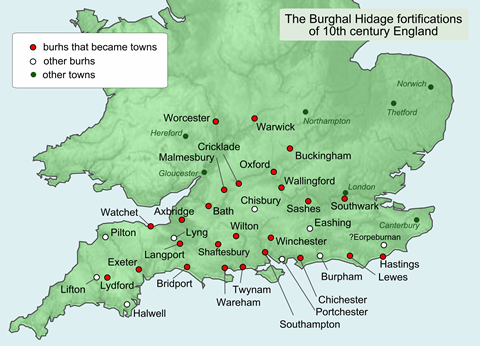

The history of new towns in Britain goes back to the Roman Empire, whose planned settlements included modern Colchester, Gloucester and York. The practice was revived by Alfred the Great, who established a network of fortified towns across southern England, either refounding Roman settlements (like Exeter) or founding completely new ones (like Oxford). These towns played a crucial role in defending the people of Wessex from the Vikings.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, scores of new towns were established, both by the royal government and by local lords. Although new towns were established across the country, the heaviest investment often went into fortress towns in areas of conflict, where they served as instruments both of defence and conquest by the Plantagenet government. Conwy and Caernarfon are examples of this in Wales.

In the later centuries, huge and splendid ‘new towns’ were often built when old cities finally burst out from their fortifications. This was extremely common in Continental Europe, where such fortifications lasted longer than they did in Britain: the Neustadt of Hamburg, the Ville-Neuve of Nancy, the Nové Město of Prague and the Nowe Miasto of Warsaw were all ‘new towns’ that have now become flourishing districts of the cities from which they originally separated. The Edinburgh New Town is the most celebrated British case of this, and Butetown in the Cardiff Bay Area has many similar characteristics.

In the nineteenth century the development of railways allowed many British cities to be ringed by satellite towns. Many of these were built around existing villages, but others were planned from nothing, like Chorleywood or Bournville. In the early twentieth century this tradition was expanded into that of the garden suburbs and cities, most famously at Hampstead, Welwyn and Letchworth.

Why have people so often planned out whole new towns rather than relying on piecemeal urban expansion? The answer lies in the need that cities have always had for public goods. Cities are profoundly reliant on a host of services that it is not normally profitable for any one individual to provide, like roads and parks. New towns offer an opportunity for providing these public goods to an extent that existing settlements normally do not, because they have one planning authority who can act in the interest of the whole community.

In the case of the earlier British new towns, the key public good in question seems to have been fortification. Anglo-Saxon towns desperately needed fortifications to defend them from the Vikings, but city walls would never emerge from piecemeal ‘free market’ urban development. Urban life could survive and flourish only if the government of Wessex invested massively in fortified new towns, or in fundamentally reconfiguring existing ones so that they became defensible.

Later new towns have specialised in providing more peaceable public goods. Many new towns have better street networks than unplanned towns, because the planning authorities designed each road with a view to supporting the road network as a whole. Many, like the Edinburgh New Town, have wonderful architecture, because their architects designed each building with a view to maximising the value of the town as a whole, not just the individual plot.

Many have excellent provision of parks and street trees, which generate no revenues in themselves, but which are vital to successful neighbourhoods. Many have more and better shopping crescents, because their designers knew that, although shops often pay less rent than housing, they are a benefit to the housing around them. All these are examples of how new towns can overcome the collective action problems that beleaguer existing settlements.

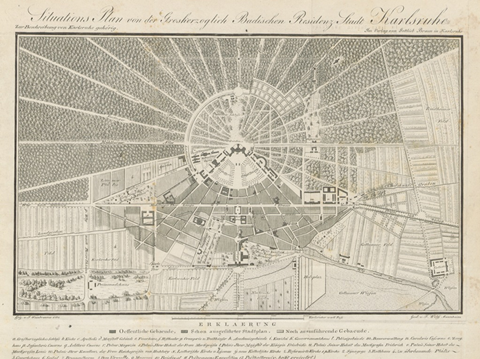

Despite this, not all new towns live up to their promise. Sometimes, this is because they are badly planned, failing to take the opportunities that unified design offers. Karlsruhe in Germany still suffers from a dysfunctional radial street network because the prince who founded it liked the idea that all its streets would radiate outwards from his throne room. Cumbernauld’s megastructure town centre, linked to the surrounding neighbourhoods by elevated concrete walkways, was a good faith attempt to mitigate the impact of cars on public spaces. Sadly, it does not seem to have worked well, and the local council now plans to demolish it.

However, the most serious problem often faced by new towns is a poor choice of location. In 1286 Edward I founded Nova Villa on the southern shore of Poole Bay, giving it extensive privileges and ordering royal planners to lay out its streets. The charter was issued, the streets were laid out, and then – nothing happened. Despite the King’s investment, Nova Villa just wasn’t as attractive a location as Poole. Today, the only remnant of Nova Villa is a farmhouse called ‘Newton’, a translated and contracted version of its grandiose Latin name.

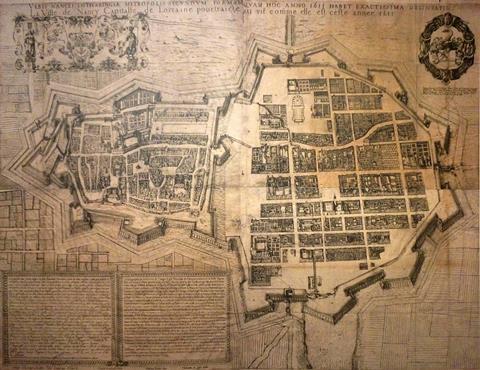

In 1631 Cardinal Richelieu, one of the most powerful men in Europe, decided to build an ideal town as an ornament to his country palace in the Loire Valley. Thousands of builders worked for eleven years to build the physical fabric, and extensive financial inducements were offered to encourage people to settle there. Despite this, Richelieu (for so the town was named) never really took off: there was no economic reason for there to be a town there, and the residents remained heavily reliant on the Cardinal’s subsidies. After his death, the town declined, and grass grew in its architecturally perfect streets. Richelieu remains obscure and quiet today.

The importance of location is also clear from Britain’s more recent experience of new towns. The intention behind the New Towns Programme was to meet the housing needs of Britain’s growing economic centres. Politics sometimes prevented planners from realising this, but when it did not, the New Towns tended to work well.

This was true even when their design was imperfect. Few today would claim that Milton Keynes is a model of walkable urbanism, but it is nonetheless prosperous and sought-after: whatever its drawbacks may be, they are trumped by one overriding attraction, namely easy access to the great employment centres of England along the West Coast Main Line.

Something similar is also true of many of the early new towns like Stevenage and Crawley. The new towns that have struggled have been those where there was little underlying economic justification for their location, leaving them permanently in need of some form of subsidy.

What is the recipe for getting location right? The most consistent class of successes seem to be new towns planned alongside growing existing settlements, huge urban extensions with their own urbanistic identity. As noted above, this often happened historically when cities that had become overcrowded behind their fortifications were finally allowed to burst out from them.

Strangely, green belting means that Britain has a number of places today in a situation rather like this: cities whose populations have grown hugely have hardly expanded outwards for decades, and now have a great deal of suppressed demand that might best be met in the form of a large, coherently planned new town rather than piecemeal extensions. The Department has already begun work on a version of this with its Cambridge New Town. The new government might look at York, Bristol and Oxford.

The other great class of successes are cities that, though physically distant from major economic centres, enjoy excellent transport connections to them. In the past, this has been a very normal mode of operations: the progressive western extension of the Metropolitan Line was entirely funded by building what are effectively small new towns around railway stations in the Chiltern Hills.

This model is still theoretically possible, but today’s Britain struggles to build new railways. The easiest way to start might be by removing bottlenecks on existing railways and then using the increased capacity created to add new stations with towns around them. Crossrail 2 offers immense potential for this in the medium term, but there may be bottlenecks that could be fixed more swiftly.

None of this is to suggest that new towns are the whole solution to the housing shortage. But they could play a valuable role. New towns need to be ‘gently dense’, mixed use, highly walkable, with outstanding public transport and popular architecture. But above all, they need to be in the right place.

Postscript

Samuel Hughes is a research fellow at the University of Oxford. He has worked on housing policy in a range of think tank and civil service roles. Previously he studied at Cambridge, Notre Dame and Tokyo.

3 Readers' comments