From its sustainable credentials to its enduring aesthetic appeal, Satish Jassal examines the enduring relevance of bricks in today’s built environment

Apparently, even a brick wants to be something. I’m not sure a brick sits and asks itself what it wants to be. Only human beings can do that.

Many years ago, a friend and I decided to visit Cambodia in search of sun, sea, and ancient temples. It was a much-needed escape from the grind of 70-hour working weeks, mostly spent on competitions.

My boss had a knack for strolling over at 5:50 pm with impromptu design critiques, leaving us scrambling on pointless redesigns late into the night. We felt trapped in an endless loop, living out our own version of Groundhog Day.

In Siem Reap, we visited around 15 temples scattered deep in the Cambodian jungle. Initially, I eagerly sketched, captivated by the magnificent peacock-feather-shaped spires rising from the jungle like flamboyant monuments, proudly adorned with intricate carvings.

Yet, over time, nature had begun reclaiming these structures, gracefully pulling them back into the earth from which they emerged.

By the seventh temple, the oppressive heat and relentless dust began to wear us down. The excitement of discovery had waned, and my sketching hand, weary and anxious from heat exhaustion, finally gave up. It was then, in my fatigue, that the temples revealed their true essence.

The later temples, further from the epicentre, were simpler – less iconic and more modest. These structures, stripped of their grandeur, defined courtyards and gathering spaces.

Their carvings were mostly gone, looted or eroded over time, leaving only sandstone bricks stacked with quiet ingenuity. These uniform bricks were turned, stacked, twisted, angled, and etched, creating elegant, rational forms.

The sandstone bricks were transported via a canal network and quarried from a nearby mountain. The Cambodian architects, deeply familiar with the material, understood its properties and maximised its potential.

What struck me was the infinite possibility within this simple modular system – an observation that, though obvious, felt profound at the moment.

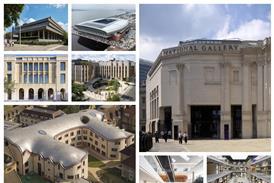

Today, my go-to material is usually clay bricks. Sourced as close to the site as possible and subject to availability (and the client’s specifications), a clay brick, like the Cambodian sandstone bricks, offers endless possibilities.

They possess a variety of characteristics, connecting closely to the earth while being crafted at a scale that feels inherently human. It’s a material that can be turned and bonded in a variety of ways, shaped either at its formation site or directly on-site by the hand of the craftsperson. These processes combine to create a material that is both robust and enduring.

Clay bricks age gracefully, and when paired with lime mortar, they can be dismantled and reused even after centuries. This makes them a low-carbon, sustainable choice over their lifetimes. Efforts are being made to reduce the carbon-intensive firing process, which we are following closely. While bricks have a long and storied history, I believe their potential is far from exhausted.

For a time, however, bricks fell out of favour, eclipsed by the allure of new cladding materials that better suited the modernist obsession with the shiny and novel. Yet many of these new industrial cladding materials, often celebrated for their aesthetics and quick installation, have proven to lack durability. In fact, according to my insurance broker, “cladding” has become a dirty word in some circles, tarnished by its association with short lifespans and failures, regardless of the actual material.

It doesn’t matter if buildings start to look similar; what matters is the quality of the spaces they define and the lives they enhance

Thankfully, the humble clay brick has made a comeback, a testament to its enduring practicality and beauty. There are multiple colours and shades to choose from, not just buff. This revival comes at a time when architectural trends are shifting.

The era of each project being radically different – often as if designed by entirely separate architects within the same office – has come to an end. The relentless pursuit of novelty for its own sake and the tendency for architects to impose ego-driven “look at me” buildings on our environments are no longer sustainable.

Instead, we are moving toward an epoch that prioritises a deep understanding of local context, materials, environment, and vernacular. This approach fosters designs that are not only appropriate for their places but also sustainable.

When architects use material palettes that suit the environment and the building’s purpose, they create designs that are both efficient and appropriate.

It doesn’t matter if buildings start to look similar; what matters is the quality of the spaces they define and the lives they enhance. Most buildings, after all, should serve as high-quality backdrops to places that are animated by the people who inhabit them.

We don’t need every structure to be iconic. There was a time when architecture seemed obsessed with this idea, like two narcissists locked in a hall of mirrors, each trying to outshine the other’s reflection. But now, we are beginning to remember that the quiet dignity of materials like clay brick can shape not just buildings, but better places for people.

> Also read: Rowan Court: a blueprint for council housing that repairs the urban fabric and elevates its context

Postscript

Satish Jassal is director of Satish Jassal Architects. He is a design expert associate for the Design Council, sits on the Harrow design review panel, is a Fluid diversity mentor and a trustee of CDS Cooperatives housing association.

No comments yet