Keir Starmer’s government has put planning reform at the heart of its ambition to get Britain building, to the delight of many developers. Daniel Gayne looks at the proposals announced last month and assesses their chances of success

Well, that didn’t last very long. Just before Christmas, Michael Gove stood up in front of a room full of journalists and built environment professionals at the RIBA’s head office in Marylebone to announce his long-term plan for housing.

His National Planning Policy Framework turned out to be decidely short-term in the end. But, while it lasted for just eight months, many in the housebuilding sector will tell you that this was time enough for it to do plenty of damage.

Now many of its most substantive changes are gone, replaced with a refreshed document cooked up by Angela Rayner, Matthew Pennycook and the rest of the team at the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (the DLUHC moniker having also been consigned to the scrap heap). This is not a whole new document – just a very substantive revision.

Helpfully, if a little unusually, the ministry published a “tracked changes” copy of the original document to demonstrate the extent of the alterations. So, Building Design has sifted through the polished-up framework, and the associated consultation documents, to find out what is now in and what is out.

OUT: ‘Beauty’ and the ‘beautiful’

Some things really stick out when you share “tracked changes”, and one of those is when someone has combed through a whole document to remove every instance of a word. Keir Starmer had been sounding almost Govian in the run-up to the general election, with his talk of building new towns replete with Georgian-style townhouses.

But, when the new NPPF document dropped, one of the starkest amendments was the removal of all references to “beauty” or the “beautiful”, which consequently triggered outrage from some on the (now much depleted) Conservative benches.

Speaking on BBC Radio 2, Rayner defended the decision, describing the inclusion of “beauty” in the NPPF as “ridiculous” and “subjective”. She explained: “Beautiful means nothing really, it means one thing to one person and another thing to another […] all that wording was doing was preventing and blocking development and that’s why we think it is too subjective.”

She also said there were plenty of provisions within the planning framework to ensure that development would be in keeping with the local area. “So there are rules and protections in place,” she added.

There is no doubt that the concept is vague and subjective, so much so that it is questionable whether it was really holding back development in any meaningful way. One wonders whether this was more an effort on the part of Rayner and co to draw a clear red line between her and her predecessor.

Within the limited specific design guidance contained in the NPPF, there were some small changes. The previous NPPF detailed that mansard roof extensions should be allowed “where their external appearance harmonises with the original building”, and that it should emulate the local style of mansard roofs from the time of the building’s construction. This lengthy, aesthetic rule has been replaced with a short parenthetical note explaining that mansard roofs are included as encouragement to allow upward extensions where the development is consistent with the form of neighbouring properties.

They also propose to remove a paragraph which says that significant uplifts in average density of residential development, occurring as a result of minimum density standards, “may be inappropriate if the resulting built form would be wholly out of character with the existing area”.

IN: A definition of grey belt

Labour ministers have been talking about the grey belt since April, but without putting much meat on the bones. It was clear that they wanted to find a way of pressuring local authorities to agree to release more of their green belt land for development and saw this concept – which refers to “ugly” parts of the green belt – as a foot in the door. But until the NPPF, it had been only very vaguely defined, and was concerningly close to the vague subjectivity for which Rayner criticised the inclusion of “beauty”.

Building magazine and others have done their best to get to the bottom of what “grey belt” actually means, and how many homes it might deliver, but the NPPF finally gave us an answer – at least to the first question. For the purposes of plan-making and decision-making, “grey belt” will be defined as:

“[…] land in the green belt comprising previously developed land and any other parcels and/or areas of green belt land that make a limited contribution to the five green belt purposes […], but excluding those areas or assets of particular importance […]”

How many homes can be built on the grey belt?

Government statistics show that, by the end of March 2023, green belt covered around 12.6% of England’s land area, totalling 16,384km2. It was introduced nationally in 1947 with the intention of preventing urban sprawl, but it has been criticised by some for blocking development on ugly, disused sites.

Such sites, which might include former storage yards, disused quarries, car parks and caravan parks, have recently been given the label “grey belt” by the Labour Party.

There are some suggestions that the label has the potential to shift attitudes to development. London-wide polling by Stack Data Strategy, conducted in January 2024, found that, among those who said they were opposed to more homes being developed in their own local area, 57% said they were opposed to building on green belt land, with 20% neutral and 24% in favour.

Asked instead whether they would support building on grey belt land, the answers were much more balanced. Around 36% came out in support, with 27% neutral and 38% against.

So it’s a good marketing trick, but is it good policy?

Well, the vast majority of the green belt is undeveloped and largely used for agriculture, but around 6.8% (as of 2022) has been developed in some way. Roughly half of this is accounted for by road and other transport infrastructure, most of which is hardly likely to be suitable for development, while the rest is comprised of residential, minerals and mining, storage, warehousing and community buildings. That’s a shade over 550km2 of land.

Unique rules already apply to brownfield land within the green belt – sometimes referred to as PDL (previously-developed land) – which will account for a portion of that 550km2. Estate agents Knight Frank have identified 11,205 PDL sites across the country, with just over 40% sitting within the London green belt.

Meanwhile, Merseyside and Greater Manchester green belt offered the second highest number of available sites. It estimates PDL sites could accommodate a maximum of 200,000 homes.

But Labour has now made it clear that grey belt is intended to free up green belt development beyond the PDL cateogry. The current definition of PDL excludes agricultural or forestry buildings, as well as land used for mineral extraction – and these could be areas that local authorities look to bring forward in green belt reviews.

Property business LandTech has had a crack at its own estimate of how much potential there is to build on grey belt. It made its assessment prior to the NPPF’s publication, but its methodology fairly well reflects the definiton settled on by the government.

Without anything resembling a grey belt dataset, it identified PDL sites using the Brownfield Land Registry and other vacant or derelict sites based on data from Ordnance Survey and HM Land Registry. It took a relatively conservative approach, only considering sites adjacent to existing roads and built up areas, ruling out the most isolated sites.

It also ruled out sites that are significantly affected by flooding, protected as sites of special scientific interest, priority habitat, nature reserves, common land, ancient woodland, best and most versatile (BMV) agricultural land, or scheduled ancient monuments.

According to this methodology, there is potentially between 87 and 106km2 of quality grey or brown land within the green belt. On the assumption of 60% site coverage, to allow for some biodiversity net gain to be delivered on site, LandTech estimates that between 52 and 64km2 of this is developable.

On an assumed density of 50 dwellings per hectare, it estimates a potential to deliver between 261,000 and 318,000 new homes.

Remember, Knight Frank estimated that green belt PDL alone could yield only 200,000 homes at best. Combining these two guesses would put the additional housing potential of grey belt – as a category distinct from existing brownfield sites within the green belt – at between 60,000 and 120,000.

Areas or assets of particular importance include sites of special scientific interest, local green space, areas of outstanding natural beauty, national parks, heritage coast, irreplaceable habitats, designated heritage assets and areas at risk of flooding or coastal change. And, for those of us who need reminding, the five green belt purposes are:

- to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas

- to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another

- to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment

- to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns

- and to assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.

So, to recap, grey belt is anywhere in the green belt – excluding those areas of particular importance – that makes only a limited contribution to those five green belt purposes. For many, that may seem not massively clear, but fortunately the consultation documents issued alongside the revised NPPF do shed some clarity.

They explain that land which makes a limited contribution to the green belt purposes might have at least one of the following features:

- it contains substantial built development or is full enclosed by built form

- it makes very little contribution to preventing neighbouring towns from merging into one another

- it is dominated by urban land uses, including physical developments

- it contributes little to preserving the setting and special character of historic towns.

The challenges of building grey

Even after Labour’s proposed changes to the NPPF are adopted, bringing forward grey belt land will not be short of challenges. The ugliness of many of these former petrol stations and industrial warehouses is often more than skin deep – with pollution issues requiring costly remediation.

“Even if they do open them up for development, it doesn’t mean that developers are going to be able to actually build on them,” says Anna Beadsmoore, partner in the complex property and casualty team at McGill and Partners.

This feasibility question will become even more significant if Labour wants to be serious about keeping green belt development in line with its five golden rules, which include commitments to social infrastructure and a high proportion of affordable homes.

Ian York, planning director at Lichfields, speculates that commercial considerations may force developers to eat into bona fide green space in order to create schemes that will remain profitable while meeting the government’s requirements.

“If you need that kind of social infrastructure alongside 50% affordable houses, then I think you are inevitably going to be directed, whether you like it or not, into looking at some larger sites as well,” he says.

“It might be that the starting point is to identify poor quality and ugly areas, but then you might consider how, next to those sites, you might be able to deliver more strategic development to meet those high levels of affordable housing and deliver those services and infrastructure.”

Beadsmoore also raises concerns that the policy could create incentives for landowners to let buildings on their land go to seed in order to be able to sell it to developers. “There are concerns from a lot of property professionals and local residents around the fact that you can make anything pretty ugly and unusable,” she says.

Beadsmoore also notes that historic legal agreements that often exist on green belt land could create yet another obstacle for developers.

“A lot of this land has probably got mines and minerals excepted, which means that, back in the day, the lord of the manor would sell off parcels of their land. But they would say, ‘We’re still going to maintain mining rights on your land so that, if there’s a coal seam found under it, we’re still allowed to mine that’,” she explains.

“Now there’s not that much mining going on in the UK but, because you don’t own that, as soon as you pile into that land, you are trespassing.” Such agreements can stop development dead in its tracks, but it is more likely to force a negotiated settlement, which could include a share of developer profit.

As well as mining rights, green belt land is commonly impacted by restrictive covenants – whereby previous landowners have agreed to sell up on a particular condition. Such covenants might insist that the land be used as a single private dwelling or prohibit the development of office blocks.

Beadsmoore suggests that these covenants could be used by descendants to extract a negotiated settlement or – by well-informed local nimbys – to block developments altogether.

Finally, she notes the risk of judicial review if policy is not clear enough.

Planning consultancy Lichfields has suggested that this definition raises the potential that very significant areas of land that are “urban fringe” might be considered grey belt. “Ultimately, how much land is defined as grey belt will depend on the guidance and, probably, how (and perhaps who) carries out [green belt reviews],” it adds.

Either way, grey belt will be the last category of land looked to in a sequential test that local authorities will be required to apply when setting out plans to meet housing targets. Brownfield will be prioritised, with amendments to paragraphs 124c and 154g of the NPPF reinforcing the expectation that development proposals on previously developed land (brownfield) should be viewed positively and make development easier on such land.

They have also proposed to weaken the test for whether limited infilling or the partial or complete redevelopment of previously developed land is acceptable on the green belt.

Grey belt development will also be required to meet a set of golden rules, including at least 50% affordable housing “subject to viability”, necessary improvements to local or national infrastructure and provision of new, or improvements to existing, green space.

IN: Ambitious - and mandatory - new housing targets

These are perhaps the most consequential changes that Labour proposes to make to the NPPF. Where Gove reformed the framework to change the outcome of the standard method for assessing housing need to be “an advisory starting point” from which “exceptional circumstances” could justify deviation, under Rayner’s rule the targets would be mandatory.

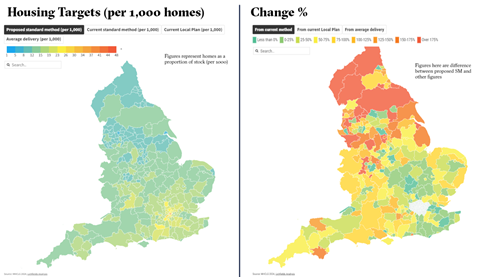

What is more, the targets will be underpinned by a new standard method, which will require 90% of local authorities outside the capitals to build more. Some of the biggest increases in assessed housing need will be in areas like the North-east, North-west and East Midlands, although ministers say that this will really be bringing them in line with other parts of the country, rather than overburdening them.

They point out that in some of these areas actual delivery had outstripped need, as assessed under the previous standard method.

According to the consultation document, in 37 local planning authorities, housing delivery is at least double their targets. “This does not make sense in a world where all but one local planning authority area has a house price to earnings ratio of more than four,” it says.

On the other hand, targets in London will drop significantly – mainly as a result of the scrapping of the urban uplift. Under the previous method, London had been expected to deliver 100,000 homes annually, constituting almost a third of nationwide housing need, and Michael Gove seemingly delighted in publicly flogging mayor Sadiq Khan for his administration’s failure to come anywhere close to this. In his later days in office, Gove had threatened to intervene directly and take over the London Plan.

The new target for London is around 80,000, which is still substantially higher than the 53,000 accounted for in London’s local plan and the 35,000 actually built last year in the capital. Despite the scrapping of the urban uplift, in areas outside London the new stock-based formula resulted in target increases of more than 30% across mayoral combined authorities, according to consultation documents.

Explaining the standard method

The current standard method is based on a four-step approach.

Local authorities are required to assess the 10-year average population growth rate, with the current year as the base and using projections based on 2014 household data.

They are then asked to apply an uplift, based on the latest median workplace-based affordability ratio.

If the strategic policies for housing in an existing plan are less than five years old, they may be able to apply a cap at 40% above the current plan requirement. If the current plan is older than five years, need can be capped at 40% above whichever is higher of the current plan requirement or household projections.

The fourth step is the urban uplift of 35%, which applies to the 20 largest urban areas nationally.

The proposed new standard method would determine need by calculating 0.8% of the current housing stock of an area and adding an uplift based on a three-year average of the median workplace-based affordability ratio, with an increase of 15% for every unit above four.

Nationwide, the new method generates a target of 371,500 net additional homes a year, up from 305,700 under the previous method and significantly higher than the 231,000 which is the aggregate of local housing targets in adopted plans.

It is clear from the consultation that many of the changes to targets are being made in the hope that more land and more consents can be brought forward than is immediately necessary to meet need. The documents explain that the government will not deliver its 1.5 million homes target “if too little land is allocated” and says that it is “starting from a point that falls far short” of the homes needed.

“We are therefore boosting the overall target to a level that provides resilience, building capacity into the system to catch up,” it continues, acknowledging that there will be places where it is not possible to meet assessed need despite taking all possible steps.

“Given that, we must build room into the formula to account for the fact that we will not see a one-to-one relationship between targets and allocations.”

ON THE TABLE: NSIP reform, changes to intervention criteria, increases in planning fees

While a great deal about Labour’s plan for planning was revealed in the NPPF tracked changes document, there were also some more open-ended points. The government is consulting on three areas where it does not currently have specific recommendations that it is looking to adopt.

The first is whether to reform the way that the nationally significant infrastructure projects (NSIP) regime applies to onshore wind, solar, data centres, laboratories, gigafactories and water projects, as the first step of a broader reform to NSIP.

The second concerns the local plan intervention policy criteria, and whether it should be updated or removed, while the third concerns proposals to increase planning fees for householders as a way of increasing resources for local planning authorities.

Regarding the second of these, the government is asking industry for its views on whether it should revise the criteria for intervention (and if so, how) or simply withdraw the criteria altogether and rely on existing legal tests to underpin the future use of intervention powers.

ABSENT: Government directly building council homes

Despite Rayner’s talk of a “council house revolution” in the run-up to the NPPF announcement, there was little in the published documents to suggest that the government is gearing up for a major programme of social or affordable housebuilding led by councils themselves – a fact which was noted both in Westminster and in industry.

David Crosthwaite, chief economist at the Building Cost Information Service, a consultancy providing information for people in the building industry, said it was “difficult to see how Labour will achieve its ambitious housebuilding targets” while private developers remain the sole source of new supply.

“Over the last few decades, many governments have tried to influence the number of new homes being built, but most have failed,” he said. ”They have no lever to control the supply since flooding the market with new homes would not be in the best interest of property developers, or existing homeowners, as carefully controlled supply maintains price levels.

“The only way the government could really influence supply would be to build themselves, which they used to do when local authorities employed direct labour to build social housing.”

However, he said this option seemed “unlikely” due to the state of public finances.

The Green Party’s co-leader Adrian Ramsey made a similar point in parliament, pointing to “a million homes that planners have allowed but developers haven’t built, too often in order to keep prices high”. He said planning reform was a distraction from the real answer to the housing crisis, which he said was “large-scale investment in truly affordable, sustainable council housing”.

On this view, it is perhaps no surprise that Rayner’s NPPF has been well received by housebuilders, with the HBF saying it has “given hope” to housebuilders and Berkeley returning to the land market on the back of it. They and others will no doubt have more to say as the consultation process rumbles on.

While the changes look set to boost bottom lines, it only remains to be seen how effective they will be in solving the UK’s dire housing crisis.

2 Readers' comments