On the day she receives the Royal Gold Medal, Ben Flatman talks to Lesley Lokko about her varied career and her hopes for the future of African architecture

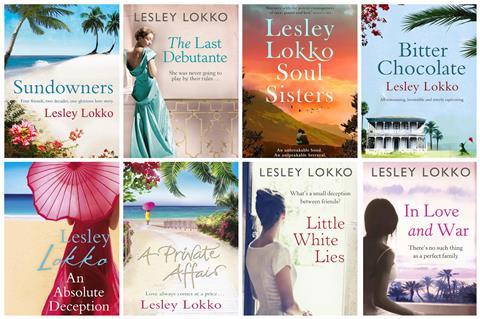

Few former RIBA Gold Medal winners can have had so varied and successful a career in parallel professional spheres as Lesley Lokko. Not only is she a respected academic and curator, who has founded a string of architectural courses, schools and institutions, but she is also a successful novelist, the author of 12 books for a mass market audience – The Scotsman has described them as “glam lit”.

In any previous era, this might have seemed inconceivable. Architectural academics are of course by necessity writers, but usually of earnest manifestos and theoretical texts. Lokko writes these too, but her fiction writing is unashamedly commercial and – on first appearances – quite distinct from her work as an architectural academic and curator.

But Lokko’s path has been far from conventional and the way she has pursued her life and career is perhaps as much her manifesto as anything that she has actually written. From dropping out of Oxford during the second term of a degree in Hebrew and Arabic, to curating a Venice Biennale that was widely seen as challenging the established narratives around what architecture is, she has made pushing back on conventional expectations her calling card.

For more than 20 years, Lokko has dedicated herself to elevating often overlooked voices and delving into the interplay of architecture, identity and race. Her work to “democratise architecture” led the RIBA honours committee of 2024 to describe her contribution to academia and the wider built environment debate as a “clarion call for equitable representation in [the] policies, planning and design that shape our spaces”.

The ease with which she apparently segues from popular culture, architectural academia and the world of the Venice Biennale seems all part of her desire to challenge boundaries and conventions. “I think they really do feed into each other,” she remarks on the relationship between her work as a novelist and career in architecture. “I mean for me, to be honest, I don’t really see a separation.”

“I recognise that there is something about never fully being one thing or the other that has always appealed to me. And I’m sure it has its roots in mixed identities.”

This sense of breaking down barriers about what is and is not architecture, and a wilful insistence on working across conventional boundaries, seems fundamental to Lokko’s approach.

‘You’re mad, you should be an architect’

Born in Dundee with mixed Ghanaian and Scottish Jewish heritage, she was raised primarily by her father. He moved regularly for work and Lokko spent a formative part of her childhood at the Ghana International School in Accra, followed by boarding school in England.

She describes her decision to leave Oxford as a straightforward one of realising that she was on the wrong course. But why then architecture? Her journey seems to have been characteristically roundabout.

“I didn’t actually know anyone who was an architect growing up,” she says. “But I remember as a child writing off to kitchen magazines and then I would get sent these catalogues. When I look back at it, I think that’s a really odd thing for a seven or eight-year-old to do.

“But there was obviously something about the image of architecture that fascinated me. And I think it came primarily because we were always moving country – and so the environment around me was constantly changing.

“And I think I was looking, maybe subconsciously, for a way to understand or process those changes. But that has only become clear much, much later.”

After Oxford, Lokko headed to Los Angeles to be with her boyfriend at the time. “It was very prosaic,” she says of her decision to move to the US, where she worked in a variety of different jobs.

“I was working for an Iranian man who ran a restaurant, and he asked me to come with him one morning to help select some countertops. I had been thinking at the time that I might do law or child psychology or something. I couldn’t quite work out what I wanted to be.

“My mother had been an art teacher so, before she left, I learnt how to draw a little bit. And I drew a quick perspective sketch for him, and he just said, ‘you’re mad, you should be an architect’. And that literally was it.”

‘I went from being a student in June to being a tutor by September’

Lokko applied to the Bartlett, which she thoroughly enjoyed. She completed Parts 1 and 2, but never registered as an architect, instead becoming increasingly drawn towards education and academia.

It was her diploma tutor, Jonathan Hill, who first encouraged her to teach. “I went from being a student in June to being a tutor by September,” she says. “I was kind of lost to practice. You either worked full-time or you didn’t.”

She went on to undertake a PhD under Hill’s supervision and he was clearly a major influence. “I realised after a semester that he was an amazing person to teach with. I never had that kind of teaching relationship with anyone else again.”

From 1997 to 1998, she served as an assistant professor of architecture at Iowa State University and, from 1998 to 2000, at the University of Illinois. In 2000, she assumed the role of Martin Luther King visiting professor of architecture at the University of Michigan.

>> Also read: Lesley Lokko - ‘I enjoy writing the sex scenes. It’s great fun!’

Following this, she returned to the UK, teaching architecture at Kingston University, the University of North London, and ultimately at the University of Westminster. It was there that she established the influential master’s programme in architecture, cultural identity and globalisation.

But Lokko grew frustrated with the academic world in the UK at the time, perceiving it as still unreceptive to a lot of the ideas that she was interested in exploring around race and alternative narratives in architecture. She left Europe again in 2002 and returned to Ghana, designing and building her own home. From there she produced 12 novels over the following 13-year period.

“In Ghana my identity was very culturally grounded,” she says. “So, you know, when I was growing up, we were Ghanaian and that was the kind of lens through which I saw myself. And I don’t think that’s changed to be honest.”

‘I suddenly thought, why not?’

But, despite a successful new career as a novelist, a chance meeting at a conference in the Netherlands in 2012 was to lead to a return to teaching. Having accepted a role as a visiting examiner at the University of Cape Town, she was asked to help publicise a new associate professorship role to her network. Instead, she decided to apply herself. “I suddenly thought, why not?”

The opportunity to work in South Africa provided opportunities to explore ideas that she felt were treated as niche in her previous teaching roles. “I had found that the landscape around architectural education at the time [in Europe] could only really view race as marginal and quite peripheral.”

This freedom to work more openly was a key part of her return to academia. In 2014-15, she established the new graduate school of architecture (GSA) at the University of Johannesburg, becoming its first director, and modelling the school’s unit system on the Harvard GSA and Architectural Association.

Lokko’s interest in race stems from a “creative interest” in how identity informs wider discussions around the built environment. “People talk about [my work] as kind of advocacy and diversity and, you know, inclusivity driven, but actually [for me] it was really about a kind of creative expression.

“It’s quite strange to now find it front and centre in a different way,” she says of the increasing foregrounding of discussion around race in academia, the media and popular culture.

What does she think has brought about this change? “There are many things, but I think Black Lives Matter was certainly an absolutely pivotal moment when suddenly the relationship between race and all sorts of other things, particularly to do with the city, came into really sharp relief.

“But I also think that, in general, literature and film, music and dance, and all of the creative arts have really expanded over the last 15 to 20 years, which is very different from when I was a student.”

The Laboratory of the Future

In 2022 the president of the biennale, Roberto Cicutto, invited Lokko to oversee the 2023 architecture event in Venice, her first curatorial job. She decided to put the spotlight on Africa, and titled her event “The Laboratory of the Future”.

At the time she spoke about the importance of recognising the “double consciousness, the internal conflict of all subordinated or colonised groups”, and sharing the experiences of underrepresented people.

>> Also read: The British Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale

“In Europe we speak of minorities and diversity, but the truth is that the West’s minorities are the global majority”, she continued. “Diversity is our norm.

“There is one place on this planet where all these questions of equity, race, hope and fear converge and coalesce: Africa. At an anthropological level, we are all African. And what happens in Africa happens to us all.”

She has spoken in the past of the story of architecture being “incomplete”, and sees it as part of her wider mission to open up discussion and shift the debate on what architecture is and can be. The biennale was welcomed by many as a necessary corrective to architectural discourses that appeared to have sidelined swathes of the world’s population.

The African Futures Institute

Part of Lokko’s mission in architecture has been to broaden horizons and discussion. “Architectural education, in particular, doesn’t easily make space for other interpretations,” she says.

But she believes important progress has been made in breaking down artificial barriers between the workplace and classroom. She believes “the antagonism between teaching and practice has increasingly dissolved” over recent years.

The desire to reframe architectural education, particularly in Africa, led Lokko to establish the African Futures Institute in Ghana in 2021, “a new kind of institute of architecture and the built environment” focused on “the world’s youngest and fastest-urbanising continent”.

The school aims to build leadership and knowledge among African built environment professionals, and also advocates for sustainable approaches to physical development.

“One of the big lessons I’ve learnt is that the vehicle through which you teach is often as important as what you teach. And by that I mean the kind of infrastructure of the organisation.

“I thrive in the classroom, but leading institutions means that you very rarely do that. Actually, what you do is fundraise and put budgets together and spreadsheets and all of that kind of stuff.”

Her realisation that her strengths and interests lie in teaching have informed the recent direction of her institute. “I know what to do to bring a certain confidence to students, often students, who feel quite marginalised,” she says.

I hope for a greater confidence in our own abilities to not only answer questions, but propose the questions

“So the African Futures Institute is a very different organisation. It’s not a school in the conventional sense. There’s no accreditation, there’s no validation.

“We run a teaching programme called the nomadic African Studio, which is four weeks long and runs twice a year in different locations around the continent. So we don’t have a physical home in the way of most institutes.

”There’s an office in Accra, but there’s no school building and it’s a teaching programme that’s for postgraduate students only. It’s a bit like a summer or a winter school.

“And the idea is, over the next five years, to bring as many African and diasporan students through this teaching programme as possible, and that they go back out into their own contexts and communities and schools and countries. And to use it as a kind of platform for change.”

How does she see the future for architecture and urban development in Africa? “There’s an enormous sense of ambition but, you know, weak leadership – intellectually, politically, culturally, the works,” she says.

“It has always been a kind of Achilles’ heel. So what I hope for is a greater confidence in our own abilities to not only answer questions, but propose the questions.

“It feels a lot of the time as if we’re answering questions that have been set elsewhere. I think it’s high time to set our own agendas.”

>> Also read: ‘How do I open up the field for others?’ Yasmeen Lari on winning her Royal Gold Medal

1 Readers' comment