As the battle over Sellar’s plans to overhaul Liverpool Street hots up, Daniel Gayne delves into the archive to find out about the original 1970s campaign to save the Victorian station

When the Shard developer Sellar revealed its plans to radically redevelop Liverpool Street last year – proposals which would see much of the existing station demolished and 10 storeys of office space built over the top of the grade-II listed Andaz hotel – heritage groups were quick to mobilise.

Plans were updated in January following the criticism, but despite tweaks - including the massing of the over-station development being pushed back to make it less prominent over the façade - campaigners are still gearing up for a fight ahead of a planning application due to be submitted in the next few weeks.

It is perhaps unurprising that heritage groups are not backing down, after all, this is a battle that they have fought before.

Set up last month, The Liverpool Street Station Campaign (LISSCA), a coalition of conservationists including Save Britain’s Heritage, The Twentieth Century Society and the Victorian Society, is the reformation of an earlier campaign group which led a (mostly) successful opposition to the demolition of the station in the 1970s.

>> Also read: Sellar reveals updated designs for £15bn Liverpool Street station overhaul

>> Also read: Seventies campaign group reformed to battle Sellar’s plan to overhaul Liverpool Street station

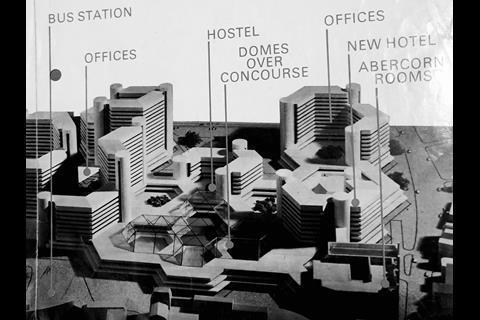

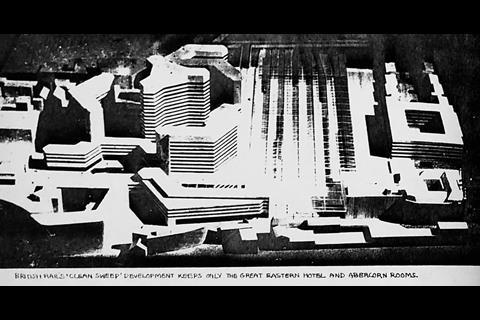

The first time around, the campaign’s adversary was the state-owned transport firm British Rail, which was pushing for an even more comprehensive demolition of the station. The plans, which it had begun formulating as long ago as 1964, would have seen the total destruction of both Liverpool Street and the neighbouring Broad Street stations and the construction of an entirely new station across the resulting 25-acre site in the heart of the City of London.

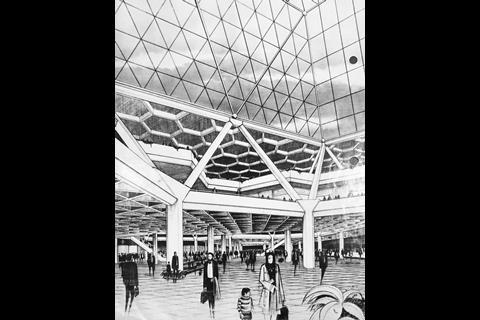

British Rail claimed the redevelopment, which would have increased the number of platforms from 18 to 22, was necessary to cope with the increase in commuter traffic resulting from the postwar explosion of suburbia, adding in promotional material to accompany their plans that foreign visitors to London could be put off by a station they described as “gloomy and unattractive”.

There was also no doubt a commercial incentive for British Rail, which was at the time under pressure from the government not to raise fares and, as the sixth-biggest landowner in the country, had a major asset to maximise. Its proposed redevelopment at Liverpool Street included more than 1.2m2 of office space and initially 135,000ft2 of office space on an “extensive raft at street level” above a new subterranean station concourse.

The Liverpool Street Station Campaign was formed in 1974, a year after a government-backed report recommended reconstructing the two stations financed by property development on the site, and in the wake of the demolition of the old Euston station in the 1960s.

George Allan, who would represent LISSCA at the public inquiry, was a “seriously under-employed pupil barrister” fresh out of Cambridge University when the campaign was launched, but with several building conservation campaigns and a public inquiry already under his belt, he jumped straight in.

He tells Building that the destruction of Euston had “galvanised the conservation movement into the need to protect historic railway stations from the deprivations of a very aggressively modernising British Rail”.

LISSCA successfully pushed for grade-II listing for the western train sheds, which was granted by the secretary of state just before British Rail submitted its initial application for outline planning permission in August 1975. The application was called in the following month, but the public inquiry did not begin until 16 November 1976, by which time British Rail had already conceded ground, deciding to retain the whole of the Great Eastern Hotel (now the Andaz).

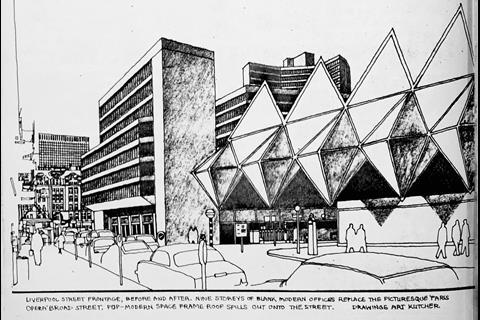

In its objection to the eventual planning application, LISSCA did not pull its punches regarding the aesthetics of Fitzroy Robinson’s early design proposals, which it described as an “arbitrary pattern of hexagons” which would “completely destroy the urban street character of the historic Roman and medieval thoroughfare of Bishopsgate”.

Its statement of opposition continued in this verbose and scathing mode: “The projection of the plan skywards to random heights produces a meaningless, incomprehensible and ultimately repellent conglomeration of nevertheless monotonous architectural forms, uniformly clad in predictable office fenestration with attendant service towers […] the modish and structurally meaningless outward canting of the lower storeys with triangular raking members completes the picture of a tired pursuit of novelty in a fundamentally shallow and cheap design.”

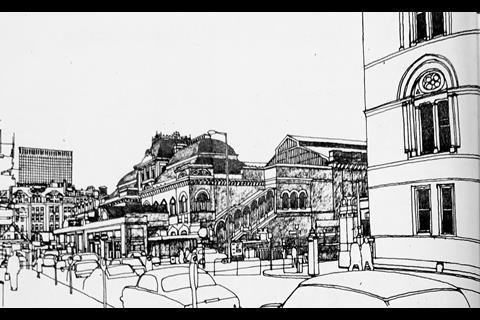

What British Rail characterised as gloomy and unattractive, LISSCA insisted was “among the most exciting architectural experiences in London”.

Much like today’s campaign, the original opposition was a coalition of conservation groups – including the Victorian Society, Great Yarmouth Society, Southend Conservation Area Society, and the Tower Hamlets Society – and harnessed the publicity draw of cultural celebrity. While the modern incarnation has TV comedian Griff Rhys Jones, the 1970s campaign turned to the poet laureate, Sir John Betjeman, and actor-comedian Spike Milligan.

Betjeman, who had his wedding breakfast at the Great Eastern Hotel, provided ample poetic descriptions of Liverpool Street for the campaign to use, describing it as “a cathedral of coupled iron columns”. In a 1975 interview with The Observer, he said he was determined that Liverpool Street should not be replaced by the “slabs and cubes of high finance”, adding: “Old stations are places of great joy because of greetings, and great sadness because of partings. They are part of the lives of a nation.”

But he did not take an active role in the campaign, according to Allan – a recollection borne out by the papers of campaign secretary John Chesshyre, which are archived at the Bishopsgate Institute in the City. In one slightly absent-minded communique from Betjeman to Chesshyre in 1976, the poet writes: “owing to too many letters and too much publicity lately, I missed an invitation that must have been sent to me to attend the inquiry about the future of Liverpool Streeet Station. Can you let me know what was the result of it?”

We were on the back foot, hence why we had to go out and hire railway consultants and so on to question everything down to the last nut and bolt

George Allan, LISSCA’s legal representative at the public inquiry

One constant challenge for the group was money. Allan recalls how, at one point in the inquiry, a member of British Rail’s legal team stood and “grandiloquently” suggested that, in view of LISSCA’s commitment to saving historic buildings, it should donate its entire funds to the rail operator to assist with preservation efforts.

“I responded by saying we would be very glad to make over the entire contents of our bank account to British Rail immediately,” Allan smiles. “The fact that it was several thousand pounds overdrawn would be largely unnoticed given the size of British Rail’s deficit.”

This large overdraft was secured by personal guarantees given by a few individual members of the campaign, the income for which came mainly from membership subscriptions, of which there were around 200, and donations.

Chesshyre’s papers attest to the financial challenge faced by the campaign and demonstrate his dogged efforts to get donations from whomever he could. His letters to major banks and corporations, but also small East Anglian farms and printing firms, were mostly rebuffed – some in stark terms that indicate the mix of opinion of Liverpool Street’s aesthetic value.

One charitable trust returned Chesshyre’s letter with a terse note: “I cannot imagine a more hideous building than Liverpool Street. The sooner it is blown up the better.”

A reply from a printer in Norwich said his “first reaction is that anything which slows down progress on transforming this appallingly filthy station should be avoided”, though he charitably promised to have another look at the building when he was next in London.

Not all of Chesshyre’s efforts were in vain, however. Publicity in the Norwich Mercury brought a “generous donation from a reader in Palo Alto, California”, while support was received from Patrick Nuttgens in the architectural world and from the journalist and later Times editor Simon Jenkins.

Allan admits that public opinion surrounding the station was “fairly mixed” at the time, noting that the concept of adapting older buildings to modern requirements was “something in its infancy”.

He adds: “We were on the backfoot, hence why we had to go out and hire railway consultants and so on to question everything down to the last nut and bolt.” Indeed, much of the expense incurred by the campaign came as a result of its efforts to challenge British Rail’s technical experts on the claimed need for a “clean sweep” approach to improving the station, which was based on the postulated need to reorient the trackwork of the station by 10 degrees to the west.

At the public inquiry, which ran until February 1977, LISSCA put forward three alternative schemes prepared by Ernest Nagy and two postgraduate student architects, which they claimed showed “how the station can be fully modernised in accordance with British Rail’s operating requirements”.

Railway engineering consultants De Leuw, Chadwick & O’hEocha were employed to report on the feasibility of three alternative schemes. They confirmed that they were all feasible “in broad principle” – and the campaign received advice from quantity surveyors Tapley and Edworthy and building economists Bernard Williams Associates to compare their schemes with British Rail’s.

While LISSCA’s opposition to British Rail’s proposals was fierce, Allan remembers how it quickly became obvious that there was “a significant area of compromise could be made between the two extremes”, with Broad Street sacrificed in order to keep the western train sheds and the Great Eastern Hotel.

Robert Thorne, an engineering and construction historian who attended the inquiry as a representative of the Greater London Council’s historic buildings division, says he has a “vivid memory” of working on loose sketches of a compromise with a British Rail representative. “My memory is that this idea was shown to the inspector who was holding the inquiry as a possible solution,” he recalls.

This, Thorne says, meant that, when the inquiry came to close with the rejection of the proposals, there was nonetheless a sense between the GLC and British Rail “as to what the way forward might be”.

It took more than a few years to get there, with British Rail searching in vain for a development partner, and heritage campaigners made an unsuccessful attempt to get Broad Street listed. But the shape of the redevelopment that was eventually approved for the two stations roughly reflected the bargain described by Allan and Thorne.

Battle lines drawn as revived Liverpool Street Station Campaign prepares to fight Sellar and Network Rail

Sellar and Network are set to send proposals for their £1.5bn scheme to City of London planners next month.

The designs, drawn up by Swiss architect Herzog & de Meuron, include a 109m-tall office over the top of the Andaz Hotel, as well as a brand new station building and two-tier concourse.

The plans would nearly double the floorspace of the station and add more than one million square feet of mixed-use station above.

Conservation campaigners have come out strongly against the scheme, as has istori England, the government’s own heritage watchdog, which upgraded the station’s grade II listing to include some elements of the 20th-century rebuild and improved the Andaz’s listing to grade II*.

If approved, work could start on the scheme in the second half of 2024.

>> Heritage groups raise alarm over Sellar’s Liverpool Street plans

>> Sellar reveals updated designs for £1.5bn Liverpool Street station overhaul

>> Battlelines drawn as Historic England again lays into Sellar’s updated Liverpool Street plans

>> Seventies campaign group reformed to battle Sellar’s plan to overhaul Liverpool Street station

Broad Street was handed over to developers Rosehaugh Stanhope in 1985 and demolished the following year, eventually becoming the Broadgate office development. The proceeds from this development were used to help fund modernisation at Liverpool Street, which began in 1985.

While the eastern tractions were demolished and the overhead space used for office accommodation, the original trainsheds to the west were restored and extended to the south and a new station concourse was built, designed by Nick Derbyshire in a Victorian style.

The redeveloped station was eventually officially opened in 1991 by the Queen, with the plaudits British Rail received for its sympathetic approach striking a bittersweet note for campaigners. “It stuck in our throat a bit that, 10 years after the public inquiry when the scheme had been implemented, they got all these conservation awards for it,” says Allan.

[LISSCA] showed that, at a public inquiry, if you really knew your onions you could have an impact

Robert Thorne, engineering and construction historian

The campaign, along with other similar ones in that era, emboldened the heritage movement and led to a change in the atmosphere around conservation in the 1980s. “What George Allan demonstrated was that a voluntary organisation, essentially represented by him at the inquiry, could have quite an impact,” says Thorne.

“He was there every day, picking up on every point about the proposals […] he had got the whole thing at his fingertips. That, I think was very significant in the development of the conservation movement. It showed that, at a public inquiry, if you really knew your onions you could have an impact.”

Both men agree that the difference between the 1970s planning battle and today’s is the lack of room for manoeuvre. Unlike British Rail’s initial plans, Sellar and Network Rail intend to keep the historic western train sheds and the Andaz Hotel. Indeed, what they seek to demolish is exactly the sensitive 1990s rebuild that the campaigners had agreed to as a compromise.

“The 1970s plans were a child of their time, when the sensitive adaptation of historic buildings to modern requirements did not exist […] we are actually very good at that now,” says Allan.

Fifty years on and now an informal legal adviser for SAVE Britain’s Heritage, George Allan still pulls no punches when it comes to Victoriana. In his view, there is no possibility for a compromise this time around – Herzog de Meuron’s designs on Liverpool Street “deserve no place in the modern planning world”, he says, “and should be killed at birth”.

The institute, which is based in the City of London, aims to ”document the experiences of everyday people, and the extraordinary individuals and organisations who have strived for social, political, and cultural change”.

1 Readers' comment