The thrill of repurposing a historic building is worth the inevitable headaches, argues Hawkins Brown partner Nicola Rutt

To embark on any kind of refurbishment is to take a step into the unknown, and requires a very different mindset from that for a new-build. There is continuous dialogue between existing building and project team, sometimes calm and acquiescent, often argumentative and unpredictable. It is difficult to know how much the building will submit to the requirements of the brief, and how much it will resist. But from this struggle comes real creative opportunity.

A building’s presence goes beyond the physical and plays a part in local history, ingrained to varying degrees in the memories of local people. Many buildings are in the background and go almost unnoticed until plans are made to alter or demolish them. Often, we do not realise that we care about a building, or have some level of emotional attachment to it, until it is threatened, when suddenly our memories come rushing to the front of our minds.

The philosopher Alain de Botton describes how works of architecture ‘talk to us’ in his foreword to Architectural Voices by David Littlefield and Saskia Lewis (2007). His theory is that our attraction to a building is more than aesthetic, relating also to ‘certain moods that they seek to encourage’ and ‘an attraction to a particular way of life’ that the building promotes through its architectural features.

When we talk about the spirit of a place, we are referring to its meaning and symbolism. A town hall, for example, represents civic pride and continuity with the past. It is also a place where the experiences of the local community range from the joyous celebration of a wedding to the painful registration of a death. Working with buildings that evoke such strong personal feelings throughout the community must always be more than a technical exercise.

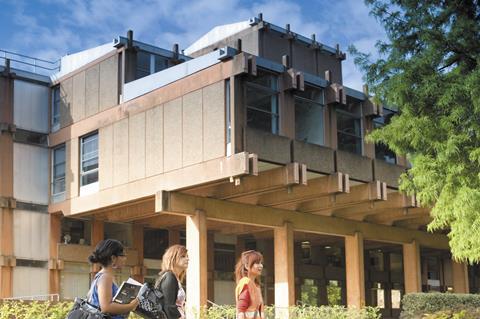

Very occasionally, buildings are ‘spot-listed’, an instant form of protection that usually occurs when design proposals are fairly advanced. In such cases the recognition of the building comes not from the immediate community, but from a more geographically remote group of architectural experts who deem it worthy of protection. The Urban and Regional Studies building at Reading University, designed by HKPA architects in the early 1970s, is an example: its spot-listing in 2016, just before Hawkins Brown submitted for planning, has led to a redesign, further respecting the building’s ‘special features’ while providing a creative and sustainable environment for its future occupants, as the client’s original brief required. At the time of writing, the building sits cold and dark while the ideas of various groups about what is important are argued out – hopefully not for too long. It is the background buildings, not those that are celebrated and ‘listed’, that are particularly tricky; they do not come with a description of special architectural features and an acknowledgement that they are important to people.

To adapt any building is to be mindful of all this, thinking beyond the bricks and mortar to the impact it has on its occupants, the local community and its wider admirers. It is important to ask how all this will affect the client’s aspirations, and whether the societal value of the reuse is being considered alongside the financial.

When we design new buildings from scratch, we can generally satisfy the brief’s basic requirements, such as floor areas and room adjacencies. But when we embark on a refurbishment we often have little idea of how the building will challenge, shock or delight before we start peeling back the layers, so it can be a reactive rather than a proactive process. The pressure of money and programme means that design teams progress in haste, and the client maintains a risk register and a contingency fund to cover unknowns; the trouble is that ‘unknowns’ are by their nature difficult to quantify. For instance, over the years we have discovered that the ‘Victorian’ building at the Roald Dahl Museum in Buckinghamshire was actually much older; and that almost all the 1,000 or so concrete openings at Park Hill were different; and we have uncovered Anglo-Saxon loom weights in a basement on James Street in Covent Garden.

It is these moments of serendipity and the process of getting ‘under the skin’ of existing buildings that render them a rich source of creativity. We learnt about the history of ‘Elephant House’ in Camden, north London, a dilapidated Victorian warehouse that was part of the Elephant Pale Ale Brewery. Then we found one of the original bottle caps buried on the site; it has since been subtly planted into the entrance door so that those in the know can proudly recall their building’s history.

Opportunities do not always come through the uncovering of historic artefacts, however. The Broadcast Centre at Here East was built with a 240-metre-long quadruple-height steel frame (or gantry) along one of its facades, with the intention of supporting ventilation units for the studios inside the building. The brief sought to demolish the gantry, until the idea of retaining it as a frame on which to stack small, individual studio units was sparked. The concept grew from an interest in Renaissance ‘cabinets of curiosities’; here was one at an epic scale. This opened the floodgates to a plethora of ideas about how it could be used. The common thread was that it would be affordable and – given its proximity to Hackney Wick, which has the highest concentration of artists’ studios in Europe – occupied by creative people. Building at a small scale to populate the gantry provided the opportunity to reflect on the industrial heritage of the site, and previous occupiers Matchbox Cars and London Cure smoked salmon, among others, are referenced in the design of the units. This is an example of a brief evolving to fit the building – and the result is a solution that would never have been conceived as a new-build.

The desire for a connection with the past is deeply rooted in the human psyche. We seek authenticity, and that is often lost when buildings are adapted. It’s a difficult balance to achieve, and we don’t always get it right. We research, listen and learn as we design; it is an iterative process and requires an open mind and lateral thinking, not just from us but also from our clients. As a friend of mine once put it, old buildings bite back!

In addition to the societal and financial value of reusing buildings, it is the value to the environment that provides the most universally accepted argument for adaptation over demolition. One of the focuses of WRK:LDN: Shaping London’s Future Workplaces (2016), an insight study by the independent built-environment organisation New London Architecture into innovative workplace design, was the provision of adaptable buildings to ensure the future resilience of the city. The report found that the ‘reuse of older buildings is in line with a greater emphasis on sustainability and a longer-term vision, while their heritage adds character that can align with and enhance the [occupying] company’s image and identity.’

Robust structures with generous floor-to-ceiling heights and large windows are inherently adaptable; the popularity of buildings from the late 19nth and early 20th centuries is testament to that. Metropolitan Wharf on the north bank of the River Thames in London is now on its third life, as a mix of studios, offices and high-end loft apartments, and it will no doubt evolve again in years to come.

Increasingly, buildings are being stripped back to their structural frame, and holes knocked through slabs to provide vertical connections between floors. This encourages collaboration among the occupants, and the subsequent cross-fertilisation of ideas – all good ingredients for innovation and creative thinking. More intimate spaces are now being created through the clever use of furniture rather than with partition walls, leading to a shift in the way we think about occupying space. New buildings are beginning to look more like stripped-back warehouses, in recognition that this is the ultimate adaptable – and therefore sustainable – model.

As a reaction to rapid changes in technology and swathes of new development, people value more than ever a connection to the past. ‘Authenticity’ is a word that springs up regularly in discussions about our built environment, probably because so much of what is built feels contrived. To arrive at a creative solution to the reuse of a building, we must cast the net wide, considering the impact on the local community and culture, the environment, the building’s possible future and its uncertain past.

It’s a battle, but one that is well worth fighting.

Postscript

Nicola Rutt is partner and head of workplace at Hawkins Brown.

This essay is taken from the new book, Hawkins Brown: It’s Your Building, with an introduction by Hugh Pearman (Merrell Publishers, £45).

No comments yet