Patrick Lynch finds that a book on Sigurd Lewerentz reveals new perspectives on the Swedish architect while also reinforcing his enduring relevance to contemporary practice

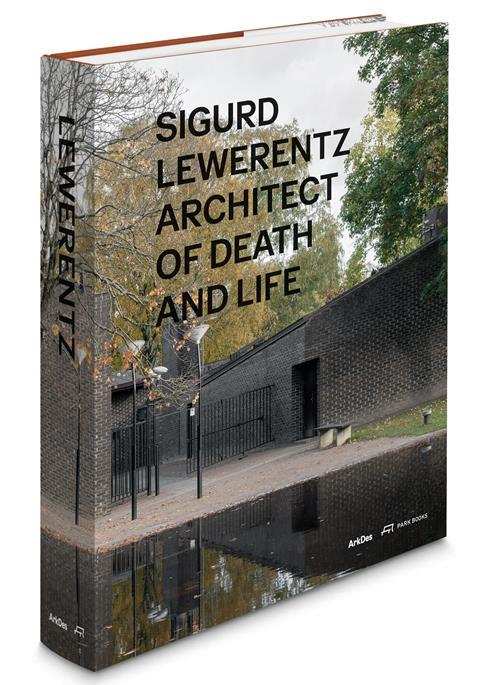

The English director of ArkDes Stockholm, Kieran Long, remarks in the introduction to the catalogue for the museum’s recent exhibition on Sigurd Lewerentz, that: “When I arrived in 2017, this project was among the first that I initiated. Lewerentz’s work was ubiquitous in the education of all the best architects I had grown up with in my twenty years of writing about, curating and teaching architecture in the UK”. However, Long notes that “books about him, most of them out of print, were kept like treasures”. And so this handsome, copiously researched and elegantly designed new book, with exquisite new photography by Johan Dehlin, is an attempt to satisfy the “extraordinary interest in Lewerentz’s work around the world”. It succeeds magnificently.

The book is organised into three parts: texts, followed by new photography and then extensive archival visual material. Long’s colleague at ArkDes, the architectural historian-curator Johan Örn, whose previous research has dealt in detail with the role of interiors in 20th century Swedish architecture, has informed the approach taken here. Örn’s essay, ‘Sigurd Lewerentz: The State of Architecture’ is organised chronologically as an “architectural biography” and draws heavily on the archive of his drawings and professional correspondence housed at ArkDes.

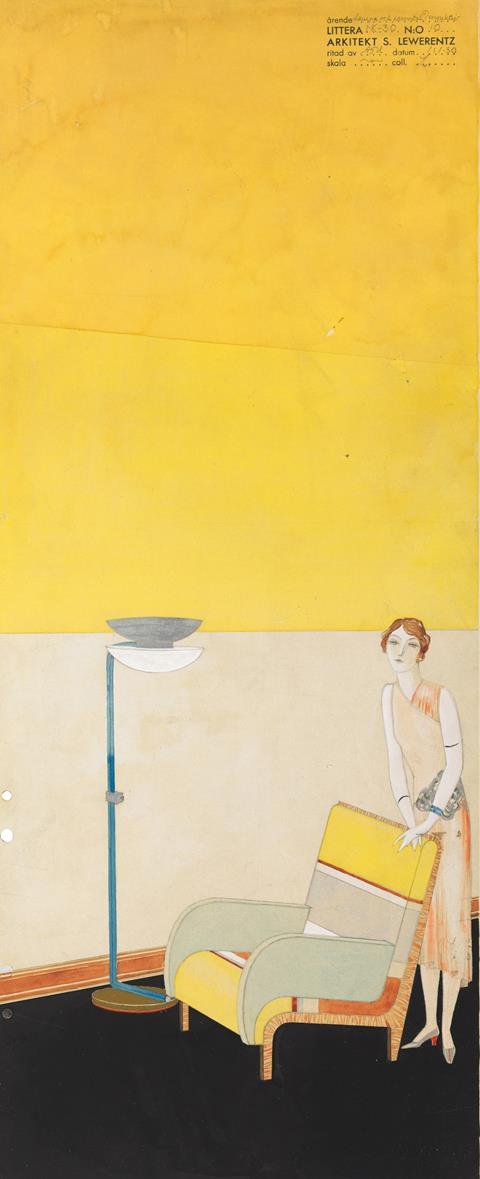

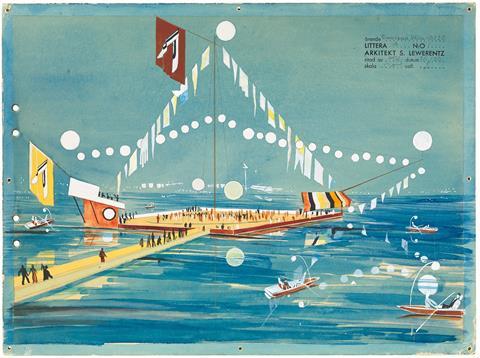

We learn that Lewerentz was seriously interested in and adept at the creation of luxurious furniture and interiors, including wallpaper even. He traces the architect’s progress from his provincial bourgeois origins, via his training at a Chalmers technical college and internships in Germany, to the flowering of his career alongside Gunnar Asplund in metropolitan, rapidly modernising 1920s Stockholm.

The final chapter, ‘Lund: A Living Legend’, documents Lewerentz’s final decade in semi-retirement as a widower. This is the image of the architect – as “a master of his trade, but also a resistance fighter” - that we are familiar with from the previous books about him, by Hakon Ahlberg and Janne Ahlin. Folke Edwards, art critic and head of Lund’s art gallery, writing in 1966 declared, “Lewerentz appears as the great liberator, the enviable Master, with free hands to create superb architectural works of art and to realise the bittersweet dream that almost every architect harbours. He has become a symbol of the freedom that has been lost.”

Örn notes though that: “Lewerentz continued to be a polarising figure. Not everyone was euphoric about the church (St Peter’s) and its ideals - one article summarising the debate was titled ‘A Goal for Dreamers?’”. Yet, as Folke Edwards put it, ‘the high priests of this Lewerentz cult are remarkably young’ and see their master ‘as equal - or even superior to - the pioneers of modern architecture”’: a claim that this book goes a long way towards verifying.

Mikael Andersson writes on the methodology employed by the curatorial team in ‘Notes on the Archive’, attesting that “Bernt Nyberg is central to the story of how Lewerentz’s papers came to the Museum of Architecture in Stockholm”. He then confesses: “The driving force behind our selection has been a desire to broaden the perception of the scope of the Lewerentz collection and to present, as it were, its ‘prismatic fringes’ - material relating to his lesser-known projects as well as things that are not usually valued as highly as the drawings…

”Early sketches - sometimes mere traces - receive as much attention as final drawings. Sometimes we have shown a series of sketches, to emphasise Lewerentz’s working methods and the way he constantly tested and re-tested ideas.” The result is a book that is over 700 pages long – a visual and tactile delight.

In ‘Sigurd Lewerentz: The Hardest of Hard Cases’, Long begins with the observation that “Reyner Banham described St Mark’s as the ‘hardest case’ in The New Brutalism (1966)”, suggesting that “the British architecture critic (Banham) was, in his own macho way, trying to evoke the rigour of Lewerentz’s buildings.” (p.21). “Hard case” is English slang for a strong man, a thug or gangster even, and this association of the initial appearance of Lewerentz’s buildings with his supposed character is I think unfortunate. It’s easy to see why these myths grew up though, particularly from the original monochrome photographs of St Peter’s and St Mark’s, and indeed from the photos of the architect on his building sites that accompanied earlier publications and exhibitions.

“In contrast to the affection in which Lewerentz is held by architects and the wider public”, Long continues, “there is a surprising lack of interest among those engaged with the history of Swedish architecture”. “Perhaps”, he muses, “this neglect can be explained by the fact that Lewerentz was not a typical architect. He made works in a variety of styles that do not map perfectly to style-based time periods… architectural historians have, in the main, not given full accounts of Lewerentz’s work.”

Progress in Swedish society as whole, and its national architecture, is often portrayed as a shift from tradition towards secularism in the twentieth century, i.e. from superstitious darkness towards enlightenment, and from Classicism to Modernism. This development is usually seen as manifest in a concomitant movement from heavy construction towards lightness. In contrast to this too-neat narrative, the late churches of Lewerentz are thick and mysterious, the fruit of the imagination of an old, religious, and somewhat anti-social obsessive. Neither they, nor their architect, fit well with the conventional Swedish national self-image.

In common with Ingmar Bergman and Astrid Lindgren, whom, despite their international critical celebrity, were often at odds with Swedish society, here is something weird about Lewerentz’s critical neglect at home, which this book brings into high relief. To a degree, the famous Swedish Model - of political tolerance, social stability and conformity - seems strangely unable to cope with outliers of huge talent and conviction like these. All three artists’ work represent a powerful spirit of free creative play, co-existing with a passionate and fastidious dedication to craft: two things that are usually seen to be in opposition in a Rationalist world view. The early critical reaction to Lewerentz by “functionalist” critics was often quite violently hostile in fact.

His contribution to the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition, carried out as part of the developer-contractor-design firm BLOKK, where he was a partner - ideal apartments for middle-class urbanites - was dismissed as “Pseudo-functionalism”, “showing off”, “pseudo-fashionable”, “architectural dandyish”. Just like the work of Josef Frank, Örn observes, it was seen as “not “masculine enough”, too bourgeois, too capitalist. The erroneous idea that brute technological functionalism is de facto socially progressive has cast a long shadow over 20th century architectural culture obviously, and the reputations of superb architects that don’t fit into this narrow materialist teleology- Frank and Lewerentz, Muzio and Lutyens, etc. - are arguably only now just emerging from this relative critical obscurity.

Örn is very good on the quotidian and daily struggles of architectural practise as a business – “… by now he was all too used to difficult, protracted commissions” – and very strong on historical facts, yet somewhat weaker on interpretation of the symbolic meaning of Lewerentz’s work. He sometimes seems (inadvertently?) content to remain trapped in the binary functionalist opposition of “purely aesthetic” vs. “practical considerations”.

As critics like Wilfred Wang and I have revealed, Kippan means rock in Swedish, and so of course the Petrine metaphors at play in both the name and form of St Peter’s Klippan recall St Mathew’s gospel. Örn’s lack of curiosity into the symbolic dimension of Lewerentz’s poetics means that the architect’s intentions and the cultural significance of his buildings remain somewhat opaque in his account.

Long cites the hermeneutic approach that I took in my book Civic Ground (London: Artifice Books on Architecture, 2017) as evidence that the standard descriptions of Lewerentz’s work as aniconic and pure materialism are simply baseless. He contends that “Creating ‘symbolism in ultra-mundane settings’ is a particularly powerful description of an architect like Lewerentz and the way he seemed to be utterly consumed by the task he was working on - whether it was a cemetery that took decades to complete, or a kiosk for the Stockholm metro.”

And he challenges the “Marxist” paradigm that dogs a lot of modernist history: “It is of course true that buildings are signifiers of wealth and power structures. But art, like architecture, is not reducible to only this”. Long cites the paradigm-shifting recent work of art historians Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood (from Anachronic Renaissance, 2010) emphasising “the potential of art to be enduringly moving across time”, suggesting that: “It is this possibility of a ‘conversation across time’ that Lewerentz holds out to us… His unique body of work, it seems to me, can best be understood as a creative resistance to the rational project of building modern Sweden… through his architecture, Lewerentz embraced the full extent of what it means to be a citizen, to be human.”

In sum, this exemplary work of archival research makes the case that Lewerentz is a much better architect than many much more famous 20th century polemicists, and one suspects that his reputation is likely to soar even higher now - at home and across the world. Lewerentz’s disciplined approach to history and cultural memory, his incredible sensitivity to the poetic, quotidian, and humane aspects of design, and his balanced approach to the decorum and ethics of creative freedom, seem prescient; and, I am convinced, absolutely relevant now.

Postscript

Sigurd Lewerentz: Architect of Death and Life, by Kieran Long, Johan Örn and Mikael Andersson, is published by ArkDes/Park Books

Patrick Lynch is director of Lynch Architects and publishing editor of Canalside Press

No comments yet