New York’s tower craze restarts following a 15-year lull as two of the city’s most famous towers race to become the world’s tallest

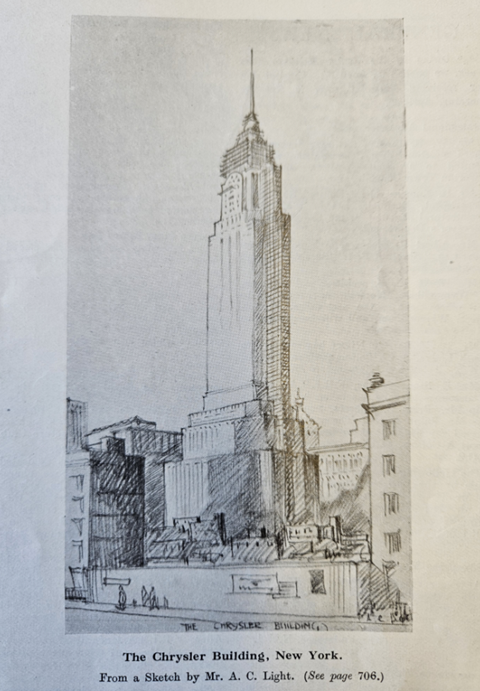

After the construction of the 241m tall Woolworth building in 1913, New York’s rush to build ever taller buildings went into a lull. It was 15 years before Big Apple builders broke another record, first with the Chrysler Building and then a year later with the Empire State Building.

International excitement around the new tower craze had been picking up. In July 1929, The Builder, the predecessor to Building Design’s sister title Building, reported a meeting of construction experts in Montreal where it was said that new towers would soon have high speed, double deck highways running along their sides and artifically lit “underworlds” constructed beneath them.

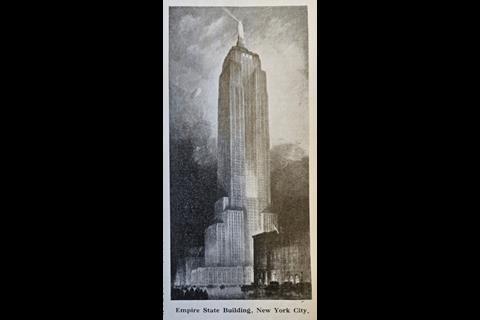

The piece below, from the following year, charts the rivalry between the two New York towers to become the world’s tallest building. Walter P. Chrysler had made it his ambition to achieve the goal, which was promptly swiped from him by the Bank of Manhattan’s Empire State Building.

The latter would be the city’s tallest building from its completion in 1931 until 1970, when it was overtaken by the World Trade Center, and then again after the 9/11 attacks in 2001 until the new One World Trade Center was completed in 2014.

Feature, 11 April 1930

THE RACE FOR THE HIGHEST STRUCTURE

MORE or less impassive during the last fifteen years, content to allow the Woolworth building to reign supreme in height, New York has again broken out into a new strife for this supremacy. From 1913 until 1928 its reputation as the “highest building” in the world has remained unchallenged. The Eiffel Tower has always been a thorn in the side of record-breaking America, and was reluctantly admitted to be the highest structure. It has now been passed by the yet unfinished Chrysler building, though the addition of a rather incongruous spire, or, more correctly, spike, was necessary to achieve this much desired end.

Between 1913 and 1928 a large number of tall buildings have been built, but none higher than the 792 ft. Woolworth tower. It is possible that the accepted fact that this latter structure failed to pay more than 2.5% on the investment prevented the undertaking of any loftier enterprises. The Equitable building was only 550 ft. high, and the Metropolitan Tower stopped at 700 ft. The Singer building attained 612 ft., whilst Detroit extended itself in the Penobscot building to reach 665 ft. Towards the end of 1928 there was a serious challenge to the Wall-street district for “skyscraper” supremacy by the 42nd-street district, around the Grand Central Terminal. Here the Chanin building was opened in February, 1929, and was quickly followed by the 10. East Fortieth-street building and the Lincoln building, all between 650 and 700 ft. high. The Woolworth building was still supreme. All were in the Grand Central zone, and it was here that the usurper of the Woolworth crown was to be built also.

> Also read: From the archives: The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911-13

The Chrysler building was originally announced to be “the highest building in the world,” 808 ft. high, containing 68 floors and being 16 ft. higher than the Woolworth building. Thus a fifteen-year record was broken, and, whether it was foreseen or not, keen competition and a heated rivalry began less than a year ago. Since then, some amazing building projects have been put forward, and some of them started. The desire for the tallest building in the world amounts almost to a passion. Of course there is the cold reasoning of advertisement value, but, even for the United States, this is stretched to impossible proportions to satisfy the conscience of the victims of the craze.

Whilst the Chrysler building was in the course of construction the startling news came from Chicago that the Crane Tower, or the Chicago Tower, was proposed to be erected to a height of 880 ft. This bombshell in the Walter P. Chrysler camp awoke it to the stern nature of the contest it had started. At no price could Chicago (in the language of the country) be allowed “to get away with this.” Furthermore, the Eiffel Tower was remembered, and it was decided to put this troublesome structure finally and firmly into the background. Every nerve was strained and incidentally every economic calculation, particularly the hypothetical return on advertisement, to the end that a new top was designed - in fact, several new tops, steadily growing in size if not in beauty, until, by means of a steel lattice-work spike, the building was stretched to the ultimate height of 1,030 ft. Instead of being 16 ft. it became 238 ft. higher than the Woolworth Tower, and this without the addition of any floors other than than the pent house type. The triumph, if any, of the Chrysler building will be short lived, as already greater schemes are on foot.

The competition was taken up by the financial district and several small lots were assembled to provide sufficient area to allow of the erection of buildings of a competitive height. The Bank of Manhattan Co. and the Irving Trust Co. entered the lists. Whilst the Chrysler Building was in the course of erection these concerns cleared sites on Wall Street necessitating, among other things, the demolition of the famous “Chimney” at Wall Street and Broadway. The Bank of Manhattan Co.’s building was planned in May, 1929, to rise 836 ft. above Wall Street, and announced as such with the smug and hopeful remark appended: “It will be the highest in New York.” This, of course, was before the Chrysler top began to grow suddenly. Not to be easily beaten, the Bank of Manhattan forced its growth, but failed to rise more than 925 ft. with 63 office floors and seven in the roof. Conditions are against the financial district recapturing the crown; the sites are too small. The attenuation of the tower of the City Bank-Farmers’ Trust Co. (now under construction) is positively alarming, as it soars to 925 ft. To understand fully the handicap of a small site it must be known that, subject to minor restrictions, the zoning laws permit buildings to run up indefinitely as a tower when the area of that tower is not more than 25% of the area of the site. It is fairly obvious that with a smaller site and therefore a smaller area tower, an economic limit of height is much sooner reached and, ultimately, structural one, too. With this in mind, returning to the mid-town district we find that, on the large site of the recently demolished Waldorf Astoria Hotel, former Governor Alfred Smith has commenced to erect the record-breaking Empire State Building. It will be finished in 1931, so that the Chrysler has exactly one year to reign before abdicat- ing in favour of ex-Governor Smith. Will the latter’s reign be as short as Chrysler’s, or as long at Woolworth’s? Already there are threats in the air.

The Empire State Building, if it does not decide to grow, will be 1,100 ft. high to the top of its 85 stories, which will be surmounted by a 300 ft. high dirigible mooring mast. Whilst solitary in its 350 ft. superiority of height, it is just possible to imagine the Graf Zeppelin or the R100 tied up to it, but, there presents itself a picture of the early future with an airship attempting to worm its way through numerous other 1,300 ft. buildings in an endeavour to tie up and discharge its passengers through the bowels of the Empire State Building into the canyon that was Fifth Avenue.

Thus after fifteen years of undisputed supremacy the Woolworth Building suddenly will have been surpassed by at least five “skyscrapers” in New York, and that by no mean margin, but generously and substantially overtopped by some 150 to 250 ft. The spring of 1931 will see completed a structure rising to very nearly twice the height of the dethroned monarch, reducing it to insignificance. The effect of this sudden growth on New York is a subiect in itself. The sudden growth is confined to the record-breaking class of building. There has always been constant building in the forty-story range during the last sixteen years, slightly accelerated towards 1928 and 1929 by the growth of the Grand Central district.

The idea will probably be scorned by the “hard-headed” American business men, but, whether he cares to admit it or not, the passion for the “highest yet” has been the incentive behind the towering heights to which the latest buildings have been forced. There has been written article after article on the height limit question, suggesting one after another deterrent to higher buildings. The structural limitation faded some time ago. Now it has been calculated that the maximum theoretical engineering height for steel frame structures, using the present formulae and building laws, is 7,000 ft. The calculated economic limitation was not so easily disposed of, though recent investigations for the American Institute of Steel Construction on high buildings states that buildings of 75 stories are not only economical but “under present circumstances” will return more on the investment than a building of 50 or 30 stories in height. Of course, it is very simple to see why this should be so assuming a sufficiently large site. It is more difficult to believe the statement that the cost of construction per floor of a 20-story building is the same as that of a 70-story one. The contractors say that financing is the only thing preventing larger buildings (by which they mean higher, as all seem to think in terms of height rather than actual size in New York). Naturally the moneylenders will wish to know firstly (and lastly), “Will it pay?” The chief deterrent to higher buildings now seems to be the inability to assemble property to provide a sufficient area of land. One hundred stories have been calculated to be about the economic limit on one city block, but in busy districts it is almost impossible to assemble a whole city block. It is strange that the onus on the city of conveying all the hundreds of thousands of workers concentrated on a few acres by the “skyscrapers,” the burden on its water supply and drainage, or the deterioration of surrounding property, does not seem to be considered as a possible limitation. As was said before, congestion is out of the scope of this subject.

This is not the end. With the moan that it is impossible to assemble even one city block under one ownership comes the news that someone (he is, of course, known) has actually assembled two complete blocks just north of and almost neighbour to the Woolworth building. The owner of this property is reported to have stated that he proposes to build on it a 150-story building, rising to 1,600 ft. above Broadway. Unless the authorities prevent it, the Woolworth building reaching less than half-way, will cower at the side of this monstrous neighbour. There are two redeeming features: one is that apparently the leases of the property do not expire for eight years, so that the proposal need not be taken too seriously. In eight years one can hope for changes in values and in the “space market” that may materially influence the height. The second ray of hope is that the authorities can and may see fit to prohibit the bridging of the street between two blocks which would be necessary to the scheme, and which it seems is expected to be permitted.

There is something in the American which makes him gaze with reverence on anything, however ugly or unattractive, which can call itself (of its particular kind) “the biggest in the world.” The smallest “city” usually manages to find something in its possession which it can call the “largest in the world,” though it very often does so without the slightest regard for truth. It is impossible to foresee to what heights their structures may soar when the strength is realised of this craze, this “record-breaking ” passion behind the undeniable financial power and constructional and financial ability of the men who build in New York.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843 - 44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873 - 1890

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886 - 89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

>> The construction of Westminster Cathedral, 1895

>> The construction of New York’s Woolworth Building, 1911 - 1913

No comments yet