The creation of ‘Instagrammable’ locations can play an important part in helping to revive struggling places, writes Trevor Morriss

Places that are both popular and ‘sticky’ share similar characteristics. Cultural heritage is sensitively incorporated; the mix of occupiers by size and sector is finely balanced and an anchor exists, supported by entertainment, to draw in footfall. And most important of all, community – the ingredient that keeps this whole layer cake together – thrives through the integration of public space.

An often-overlooked element of this recipe is that successful regeneration must also be ‘Instagrammable’. This is different from ‘experiential’. Placemakers delivering for future generations must be aware, in the way that retailers already are, that something as simple as the lack of a good photo opportunity might diminish the success of an otherwise well-crafted scheme.

The discerning eye of a social media influencer is an unlikely judge and jury, but the figures speak for themselves. Three-quarters of Gen Z and Millennials follow content creators, with Gen X not too far behind. A 2022 survey by Shopify found that 61 per cent of consumers trust influencers’ recommendations, while 56 per cent of respondents said they had bought something marketed by influencers.

In the context of Britain’s fading high streets and town centres in decline, the influence of Instagram should not be discounted. Many historic quarters across the country are struggling to attract visitors. Public funding to kickstart regeneration is limited. Decision-makers that bury their heads in the sand risk allowing the heart of their community to wither, at a time when changes to the way people interact with places present an important opportunity for renewal.

Britain is awash with a legacy of culturally and historically significant buildings. One for every 175 people, in fact. Many of these assets are highly clustered together. Placemakers seeking ways to root regeneration in a distinct vernacular and identity need look no further than to reinvent architectural assets. It could be an exhibition hall, a theatre, a community venue or a pub. You’d be surprised to find how many retail outlets, shops and parades riff off a shared inheritance as a means of distinction – and how Instagram and other social media platforms propagate the appeal of, and desire for, individuality.

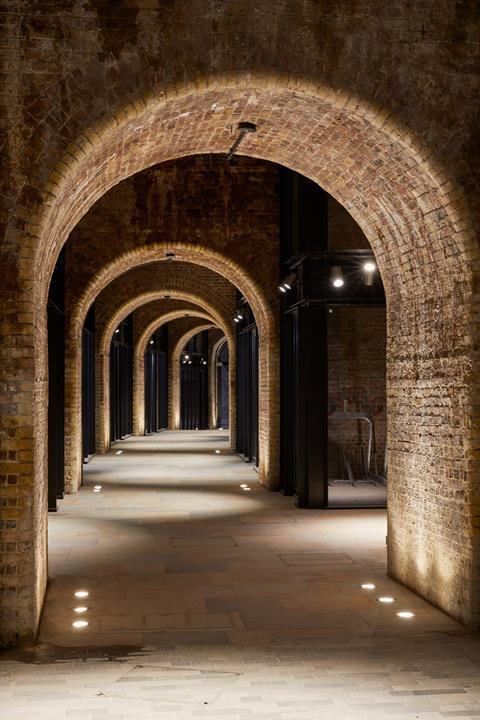

Occupiers behave in a similar way, with the desire for distinct spaces that are intrinsically connected to the identity of a local area. We recently won a RIBA Award for Borough Yards, a retail-led scheme adjacent to Borough Market commissioned for MARK, looking to bring a slice of historic fabric reinvention south of the river. Repurposing 19th century railway arches into versatile spaces for fresh food and beverage businesses and reinstating ancient footpaths, like Soap Yard and Dirty Lane was part of the apporach that we adopted following in depth analysis to inform the future of the place.

Consumers seek out unconventional ‘high street’ environments that are genuine destinations to eat, work and socialise.

When the circumstances are right to adapt, retrofit or repurpose, we should. Aside from its obvious environmental benefits, heritage is part of the assemblage that supports a coherent visual identity while enhancing an area’s appeal to a new demand informed by Instagram. On balance sheets, it should be considered a premium, not least for institutional investors and operators looking to achieve full occupancy and stabilise as efficiently as possible.

On the flipside, even in areas that are not so fortunate to have physical heritage to adapt, tapping into the cultural fibres that set one place apart from another is part of the storytelling that appeals to a social media-engaged consumer. This isn’t difficult to do with imaginative re-use of an area’s industrial context: our schemes The Candle Factory and Greycoat Stores have both been modelled on traditional handicrafts that once defined their districts.

If the aim is to generate long-term rental income from regeneration, all-the-while re-energising underserved areas, regeneration with an Instagram-friendly ‘brand’ is a question of viability, not vanity. Whether the force behind regeneration is a local authority, developer, investor or architect, there is a long-term importance to social media’s influence on our perspective on place. We’d be wise to consider it.

Postscript

Trevor Morriss is principal of SPPARC Architecture

2 Readers' comments