What happens when the built environment becomes a literal battlefield, and how does a city recover?

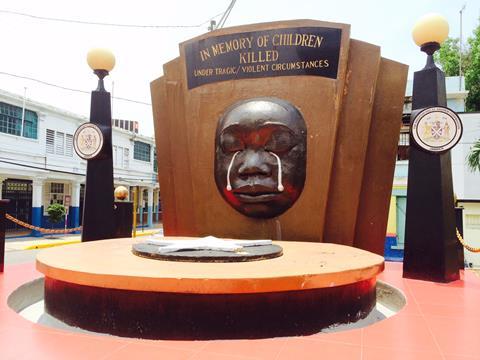

On the corner of Church and Tower Streets in Downtown Kingston stands a memorial to the hundreds of Jamaican children who have died in tragic and violent circumstances. It is a poignant reminder of the persistent violence that has blighted the city for decades. Kingston has a rich, albeit deeply conflicted history and culture but, like many cities marred by violence, Kingston’s reputation has become a major obstacle in attempts to bring about urban transformation. In Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, a sprawling epic set against the tumultuous Kingston of the Seventies, one character suggests that “Jamaica never gets worse or better, it just finds new ways to stay the same”. With outdated infrastructure, poor housing and violent crime still constants in the lives of Downtown residents, it’s not hard to understand where this view comes from. Well over 50% of Jamaicans would like to emigrate, according to recent polls. The peaceful general election in February this year suggests Jamaica is now in a period of political stability that could pave the way for a long-awaited urban revival, if it can confront and overcome the legacies from its past.

As the capital city of Jamaica, Kingston has the potential to be a key driver in the country’s longed-for renaissance and its historic and crumbling Downtown presents obvious opportunities for conservation led-regeneration. The challenge of trying to bring about positive change in a difficult urban environment is one that architects have struggled with for decades. What difference can architects make in a city blighted by poor governance and a reputation for violence? Jamaican architect Patrick Stanigar has addressed these questions over many years and is also profoundly aware of how history still defines the challenges of modern Kingston. Stanigar arrived in Jamaica at a time when simmering political tensions were about to explode into destructive urban conflict. Born in Jamaica and schooled in the US, he returned to the island in the early Seventies. He remembers a city where the conversations of privileged “Uptown” Kingston residents were still often shot through with the fear of poor black Jamaicans “rising up”.

The Kingston that Stanigar describes had been profoundly influenced by slavery. Jamaicans are proud of their multi-ethnic heritage, but the toxic legacy of colonialism still runs deep. It is sometimes difficult not to see the extreme violence and inequality that blight swathes of Downtown as partly a product of the city’s history and as a key thread that connects today’s Kingston to its past. The physical fabric of the city betrays the profound and unresolved race and class divisions that persist almost two centuries after the abolition of slavery. The city is roughly divided into two parts. Downtown is predominantly poor and black, with many residents living in dire poverty, and where accusations of police brutality are common. Uptown is more ethnically mixed, often lighter skinned, and if it weren’t for the steel grills over every window, might pass for affluent US suburbia.

In the post-independence period, Kingston’s built environment became even more profoundly politicised and contested. During the Cold War, like so many cities in the Caribbean and Latin America, Kingston became a battleground in one of the countless proxy wars between the superpowers. Jamaica’s two main political parties allowed themselves to become pawns in the wider geopolitical struggle, and cynically employed their gang-like enforcers to pursue electoral advantage through violence and outright corruption. From the Sixties into the Seventies the built environment became one of the key battlegrounds in this struggle. Housing in particular was used by the political parties to divide and control the Downtown communities.

Parts of West Kingston, close to the harbour, had been slum areas from when Kingston was first established in the late 17th century. In the Sixties, the predominantly Rastafarian slum area of Back-O-Wall was forcibly cleared and replaced by what was to become the notorious Tivoli Gardens. The project was the brainchild of the young Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) MP, and future Prime Minister, Edward Seaga. Tivoli was actually intended as a model community, with new social housing and services, but its success was fatally undermined when the housing was almost exclusively allocated to supporters of the JLP.

In the Seventies, under the leadership of the People’s National Party’s (PNP) charismatic Michael Manley, Jamaica attempted social democratic reforms to address the enduring inequality that saw Kingston home to some of the worst slums in the Caribbean. Many more new housing schemes followed, this time for the benefit of PNP supporters. These “garrisons” became no-go zones for supporters of the opposing parties. The resulting resentments and divisions were cynically exploited by an increasingly corrupt political class, and helped create profound communal and physical ruptures that continue to fester up to the present day. Like other cities torn apart through violence, both physical and invisible dividing lines can still sometimes dictate no-go areas for members of different communities.

The repercussions of these policies have resonated through the decades, including the notorious “Tivoli Incursion” in 2010, when pressure from the US forced a reluctant JLP government to send in the military to extract their erstwhile enforcer, “Dudus” Coke, from Tivoli. More than 70 people died in the ensuing violence. Graphic images were beamed around the world, reinforcing the city’s already dire reputation for urban strife.

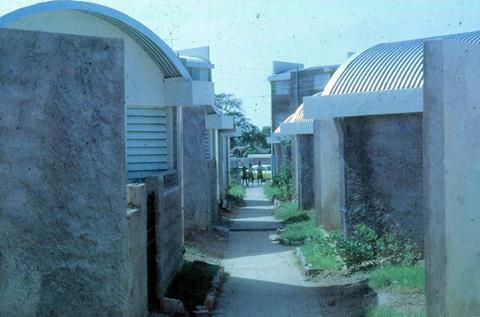

Having worked with the communities of Downtown Kingston for several decades, Patrick Stanigar’s career has closely followed the city’s recent history and also reflects evolving attitudes to urbanism. He designed one of the largest public housing projects of the Seventies at McIntyre Lands (or Dunkirk, as it became known). For Stanigar, the project was a chance to help bring about desperately needed social change. However, as many architects have found, the good intentions of social housing can easily be undermined when the allocation of housing is politicised. Stanigar later designed a new conference centre for the harbour front, in a more conventional “urban renewal”-type scheme. His later work became increasingly focused on small-scale community-led housing improvement projects and issues relating to tenancy rights and land ownership.

Stanigar strongly resents the stereotypical views of downtown Kingston. After years working among its communities he believes that all the people of Downtown have ever been looking for is a way to survive. But that doesn’t stop him believing change is essential. “I think absolutely everything needs to change”, he says of Downtown Kingston. The new government has announced Jamaica is to become a republic. Will this mark a decisive break with a troubled past? Or will Kingston just keep on finding new ways to stay the same?

Postscript

Ben Flatman is an architect whose work is mostly focused on South Asia. He lives in Jamaica and is the author of Birmingham: Shaping the City.

No comments yet