Wren and Nash had a go at imposing classical masterplans on London but they failed spectacularly, argues Ben Flatman in a riposte to a fellow architect’s recent polemic

George Saumarez Smith argues that “classicism is at the core of London’s identity”, but London (and Westminster) are built on mediaeval foundations and defy association with any one style. The Great Wen’s most rapid periods of expansion were driven by Victorian engineering and the London Underground and are more closely associated with the gothic revival and the suburban semi than classicism.

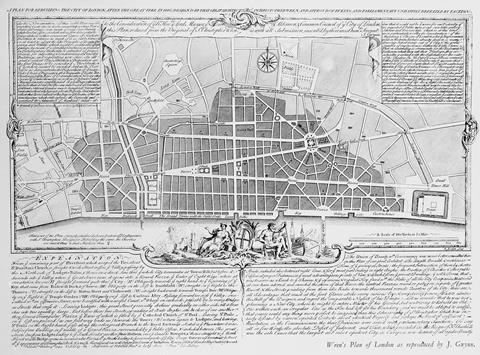

There have of course been periodic attempts to tame London’s unruly nature. Saumarez Smith points to Wren’s churches as proof of the city’s classical identity, but in truth they are only fragments of a much larger, and failed, plan to obliterate all trace of mediaeval London. Had Wren’s vision for rebuilding after the Great Fire been realised it would have erased the Square Mile as we know it and superimposed a classically inspired web of piazzas and uncharacteristically straight avenues. The commercial instincts of London’s landowners, who started rapidly rebuilding on their old plots, stopped Wren’s plans in their tracks.

Even St Paul’s itself, the pinnacle of Wren’s London, is a typically English compromise between conflicting architectural and ecclesiastical demands. Outwardly it carries the trappings of the English baroque, but its plan and liturgical arrangements are a sop to the mediaeval gothic traditions of the Church of England.

Nash probably came closest to superimposing a classical masterplan on London. Like a forerunner of Baron Haussmann, Nash used royal patronage to gouge grandiose classical thoroughfares through London’s central parishes. This was the one moment in the city’s history when classical urban design took the ascendancy, but his gimcrack theatre-set terraces have a slightly temporary and alien appearance even today.

It was during the Victorian era that London became a truly global city and underwent an unprecedented population explosion. This was when London was transformed into a modern metropolis, with grand institutions and infrastructure to match its imperial status and ambition. From the Palace of Westminster to St Pancras station and the Royal Courts of Justice, gothic revival was the defining architectural style of imperial London in its prime.

When we picture London in our mind’s eye, do we see a classical city? Not likely. Victorian literature has engrained on us an image of a smog-blanketed city of pointed archways and gothic shadows. The most famous depictions of London on canvas are arguably Monet’s paintings of Barry’s gothic towers viewed across a fetid Thames. And in the mind’s eye of millions of readers of Dickens and Conan Doyle, the physical manifestation of London is a claustrophobic cityscape of garret flats, slums and dark passageways. More gothic horror than classical urbs.

Undoubtedly there is a genuinely classical facet to the city, perhaps most evident in its 18th- and early 19th-century squares. But few would claim they represent the beating heart of contemporary London. Though pleasant enough they are largely devoid of life. Take a stroll through Grosvenor Square on most days of the week and you’ve got a good chance of being one of the only people there.

Londoners don’t flock to the stuffy garden squares of west London, now largely the preserve of international property speculators. Instead, they’re drawn in their millions to the brutalist South Bank, Borough Market and a hundred other residual undercrofts that the Victorian engineers left behind. Even messy, mediaeval Farringdon, site of human and animal butchery for centuries, draws more people than staid Belgravia.

The classical desire to control and neuter embarrassingly shambolic London was inherited by the modernist movement. Abercrombie’s Plan for London saw the East End’s “lack of coherent architectural development” as grounds for wholesale demolition and rebuilding. In an echo of Wren, the Blitz was used as an excuse to draw up detailed plans for Shoreditch and Bethnal Green that would have introduced a more “rational” plan of rigid housing blocks and neat roads. As with Wren’s proposals, they were only partially realised and much of London’s underlying urban untidiness thankfully survived.

Today’s anarchic high-rise London is therefore arguably less a rejection of the city’s “core identity” than a true reflection of its underlying character. Like our Europeanness, now casually discarded, the English have never seemed entirely at ease with classicism and its desire for order. Our only genuinely home-grown architectural traditions of the arts and crafts and high-tech both grew out of reactions against classical architecture. The most celebrated high-tech building in the City of London, the Lloyd’s building, is more steam-punk gothic than classical and seems entirely comfortable among the claustrophobia of the Square Mile’s cramped and winding streets.

Saumarez Smith has every right to assert his own interpretation of the city. But London’s identity cannot be reduced to a prevailing architectural style. Despite many having tried to impose a classical order on the city, its allure and the key to its identity lies in its heterogeneity, contradictions and glorious refusal to conform to any single simplistic definition.

6 Readers' comments