The challenges of delivering new community facilities in rural Uganda are not limited to securing first-world funding, says Ben Flatman

Living in central Kampala, the Ugandan capital, it can be easy to forget that I am on land that had until relatively recently been continuously inhabited by hunter gatherers and pastoralists for thousands of years. By the nature of its materials, including wood, earth and thatch, most of Uganda’s traditional architecture is short-lived. Few residents of Kampala would choose to build traditionally today, preferring bricks and concrete.

Although a handful of historic structures of the Buganda kingdom have been preserved, Kampala is otherwise a city of modern architecture, with more than its fair share of slums. My own home is a mid-20th-century bungalow – old by the standards of a city whose population is predominantly under the age of 30.

The absence of durable monumental structures (with some notable exceptions) in much of sub-Saharan Africa was seen during the colonial period as a sign of the inferiority of the indigenous people and their cultures, and partly used as justification for the horrors of imperial occupation. The legacy of colonialism in much of sub-Saharan Africa has meant that many architects, schooled in European modernism, have treated indigenous cultures with disdain or just plain disinterest.

The African landscape has often been treated as a tabula rasa, devoid of history or context, apart from its wildlife. Where passing reference is made to traditional architecture, in the thatched tourist lodges of Kenya and Tanzania, it tends towards the depressingly kitsch and commodified – a Lion King Disney-fied version of Africa.

In his 1979 novel, A Bend in the River, VS Naipaul describes a recently independent central African state, in which a despotic African dictator builds a simulacrum of a western modernist city. Built of sub-standard materials and ill-suited to the local climate, it rapidly crumbles and is taken back by the forest, becoming a metaphor for the shattered dreams of post-colonial Africa and its struggle to define its own path to modernity. Sub-Saharan architecture, once rich in craftsmanship and inherited environmental knowledge, is still only just beginning to feel its way towards its own identity.

It’s therefore fascinating to see how a thoughtful European architect living in Kampala today navigates architectural practice against this background of conflicted history and a profoundly ruptured culture. Felix Holland studied in Hamburg and while backpacking through Africa as a recent graduate fell in love with Uganda and decided to stay. After working for the commercially minded UK-Dutch firm of FBW for eight years, he set up on his own to explore a more diverse range of work. He now has a small office made up of mainly Ugandan staff.

One of the things that motivates Holland, like many socially oriented architects, is the desire to explore the complexities of architecture at the interface of history and culture. Two current projects have brought the practice face to face with the brutal inheritance of colonial and more recent post-colonial African history.

Kidepo National Park sits in north-eastern Uganda, in Karamoja district, which borders Kenya and war-torn South Sudan. The local people are traditionally pastoralists, known for their eagerness to accumulate large herds of cattle – sometimes by violent force. During the late British colonial period in the 1950s, in an act that seems to have created the template for future clearances elsewhere in Uganda, the inhabitants were forced out and the land was designated as a game reserve. The upheaval contributed to the ensuing famine among the indigenous Ik people. Then, soon after independence Kidepo became one of Uganda’s first national parks, but the exclusion of the local population was to become permanent.

In the decades that followed Idi Amin’s disastrous presidency, northern Uganda fell into protracted civil strife and conflict. Guns circulated freely, violence flared and the wildlife in the park suffered from uncontrolled hunting and poaching. A controversial government-initiated forced disarmament programme over the past decade has reduced the violence and once again begun to open up the area to tourism.

It’s within this context that the giant US-based NGO African Wildlife Foundation is now trying to implement a combined conservation and economic development programme. One of AWF’s biggest challenges is getting local communities to see the local wildlife as a potential economic asset, rather than a threat. AWF therefore works with local communities on education programmes and to help them develop a sustainable economy that is not in conflict with the surrounding environment.

The challenges involved in the project paint a vivid picture of the complex intersection of poverty, historic disenfranchisement and external intervention

Felix Holland Architects was appointed by AWF to design two new schools, sponsored by AWF, for the communities that sit adjacent to Kidepo. One of Holland’s driving philosophies as an architect is the importance of community consultation, which sits well with AWF’s own desire to win over the local people to their conservation agenda. However, Holland has struggled to engage the surrounding villages. Even though the new schools are being paid for by AWF, the parents of the future pupils have refused to attend consultations unless paid to do so.

The project has also prioritised the creation of paid employment for the local community but the contractor has found it hard to get labourers to show up for work. When paid at the end of the week, the men take their salaries and often then disappear for days. Listening to Holland describe the challenges involved in the project paints a vivid picture of the complex intersection of poverty, historic disenfranchisement and external intervention.

The picture that emerges is of a once self-sufficient and highly patriarchal culture struggling badly as it seeks to recover from years of interference by colonial and various post-independence Ugandan governments, with their associated upheavals and violence. Holland believes that decades of food aid during the years of conflict may have contributed to a hard-to-break culture of dependency. He notes that the only vehicles on the local roads are often fleets of white World Food Programme SUVs and trucks, ferrying aid and NGO staff throughout Karamoja.

When I speak to a WFP representative in Kampala, he partially acknowledges the damage that long-term food aid can have, but also points out that in the often arid local savannah environment starvation or malnutrition might be the alternative. He also alludes to a darker undercurrent of alcoholism and despondency that besets the area.

The architecture of the two schools in Sarachom and Geremech is appropriately stripped back and uncompromising. Drawing on locally available materials wherever possible, it uses tightly packed dry stone walling for the foundations and lower levels of the classroom walls, with compacted earth blocks and corrugated metal roofing. Carefully designed landscaping at each site seeks to create a stimulating school compound that works in harmony with the surrounding plants and wildlife.

The schools seem highly appropriate to their context and have clearly been designed with huge care and consideration to the local people. The struggles involved in getting the project built pay testament to the architects’ commitment and the perseverance of the wider community.

Hundreds of miles away, in south-west Uganda, Holland is also working on a pro-bono project with a small Batwa community. The Batwa are what were once pejoratively referred to as “pygmies” and face systematic abuse and discrimination in contemporary Uganda, as they do across much of the wider region. Echoing the plight of the pastoralists who once lived in Kidepo, the Batwa were evicted from their traditional forest-dwelling hunter-gatherer existence in the early 1990s to facilitate the creation of Mgahinga Gorilla National Park.

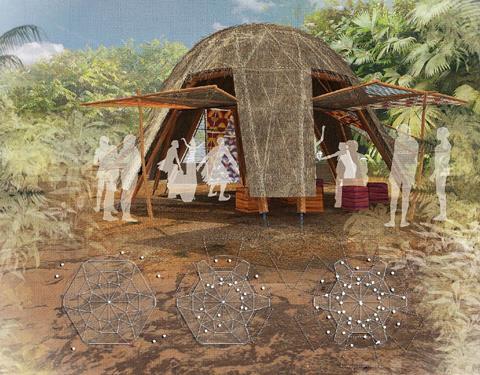

The Batwa were left completely destitute and now live a desperate existence effectively as squatters, made dependent on handouts and prostitution. Holland says that he has always shied away from overt references to the local African vernacular, but when confronted by the gross injustices experienced by the Batwa, he was compelled to draw on the fast-disappearing knowledge of their traditional forest dwellings as inspiration for a new community centre. This structure will provide a focus for a new village paid for by tourism entrepreneur and philanthropist Praveen Moman, which is motivated by a desire to offer the dispossessed Batwa some kind of long-term future.

These projects should not be seen as typical of today’s Uganda. Much of contemporary Uganda tells a compelling story of resurrection from civil war and economic success born out of adversity. But they do expose the on-going and powerful tension that still exists between the developing economies of sub-Saharan Africa and the often toxic legacy of colonialism and the sometimes dysfunctional societies that emerged from it.

As with an increasing number of other young new practices appearing across the region, FHA demonstrates the growing desire to initiate a uniquely African architectural debate that at once celebrates the continent’s huge potential, while not shying away from its complex past.

1 Readers' comment