In this edited excerpt from her forthcoming book, Dinah Bornat explores how housing design can better meet the needs of children and young people – and why engaging with them can lead to more inclusive, vibrant communities

When it comes to housing design, how often do we truly consider the needs of children and young people, beyond the play space requirements of the London Plan or the non-mandatory LAPs, LEAPs, and NEAPs guidance outside London? Probably not very often, if my experience on design review panels is any indication.

A lack of policy is likely part of the problem, but another key issue is understanding why children’s needs should be prioritised in housing design – and knowing how to address them effectively. In my book, All to Play For: How to design child-friendly housing, I aim to tackle these challenges. The book begins by reflecting on 20th-century housing, urban theories, and landscape architecture.

Inner-city mass housing was often designed with places for children to play. Along with traffic-calming measures and spacious layouts, it was intended to support and promote the community life desired by urban theorists such as Jane Jacobs, Colin Ward and others. But the concept of playable landscapes, once part of guidance, has been lost to equipped playgrounds.

There is also a strong ‘streets first’ view reinforced by many urban thinkers of yesteryear that remains embedded today. Being able to play on your doorstep ‘in sight’ of your own home, at least in policy terms, is no longer valued.

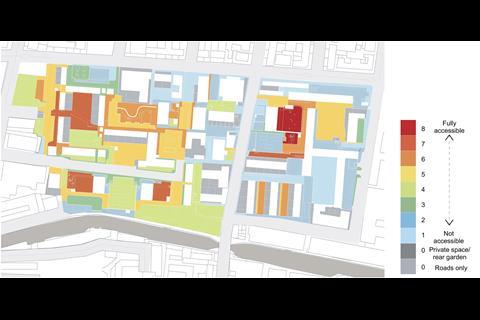

At ZCD Architects, we sought to deepen our understanding of how housing layouts can support social interaction and play through extensive observational and mapping research. This work aimed to establish a systematic approach to evaluating external spaces, focusing on how they are used by residents – particularly children – to inform more inclusive and effective design strategies.

Between 2014 and 2019, ZCD Architects carried out hundreds of hours of observational and mapping research on 21 housing estate developments across England and Wales. The studies measured the use of external spaces, particularly looking at play, as well as social use by other age groups.

The research acts as a post-occupancy evaluation tool, showing use of space and, in some cases, children’s own experience. It is a useful methodology, which shows how land can be used more effectively for social outcomes.

These heat maps are a highly effective and inclusive tool that can be used on master plan and housing projects, as they help to articulate what good layouts look like to clients, design teams and even residents. On existing estates, the maps are good at predicting where spaces are poorly used, or feel unsafe and unloved. On proposals, you can use maps to discuss how access to spaces can be improved and broaden the discussion to talk about vertical circulation, sightlines from upper floors and security.

Building on this, our practice has explored how to incorporate the voices of children and young people into the design process. Drawing on extensive engagement experience with hundreds of participants aged five and up, we have developed methods to ensure their perspectives shape meaningful and impactful outcomes in housing design.

This area of work is thriving, helped by progressive clients such as the Earls Court Development Company and the Van Leer Foundation, who have allowed us to broaden our approach. At Earls Court, this has led to an intergenerational focus that we now advocate for on all our projects.

With Van Leer, it has included the parents of the very youngest (under-fives). In both instances, we are heavily focused on the impact this type of engagement can have, thinking about child-friendly housing as more strategic, long term, and with potentially measurable outcomes.

For housing projects, the biggest impact of youth engagement is most likely to be on external spaces; these are particularly important as children and young people tend to spend more time outside, either playing or socialising. As well as focusing on external spaces, the engagement should also include how young people move around the development and the wider area. Indeed, their input may stretch beyond the site itself into surrounding streets and spaces.

Engagement needs to demonstrate impact, and this can be achieved through several means. Professionals must advocate for a broader approach than just outcomes, making sure the process itself is impactful. To do that, start with good dialogue, which leads to trust and, in turn, impact.

Designing housing with children and young people in mind doesn’t just benefit them – it enhances the quality of life for the entire community

It is equally important for young people to be heard by other people in their community as it is by those with the power to make change. Intergenerational dialogues offer an opportunity to emphasise needs and see where they overlap.

In housing, bringing children and young people into resident participatory groups can be transformative; it changes the dynamic and has the potential to avoid and resolve conflicting needs.

At the briefing stage, avoid a ‘blue skies’ or ideas-focused approach to design, as this raises expectations that can’t be met, resulting in inevitable disappointment. Instead, try creative techniques to focus conversations on what matters to the young people. Through these conversations, start to draw out design ideas and solutions together; this is a form of co-design, rooted in lived experience, where the designer is guiding the process with their skills.

Close working in this way gives space for young people to become ‘real’ to the design team, who can then draw on them when considering complex issues, rather than just relying on their own lived experiences. The design team will be able to advocate for them, away from engagement sessions, and will ensure that the needs of children and young people are paramount.

Long-term strategies and thinking tap into social value objectives, which are increasingly seen as essential parts of the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) goals that organisations and indeed local authorities should be embedding into their processes. Good engagement techniques could be used to create much-needed evidence that could form part of a more rigorous and inclusive approach to local plan making, whereby children’s needs are understood and framed before development processes are begun.

And a more universal application, such as Sweden’s implementation of the UN Convention on Rights of a Child, would mean all communities could benefit, not just a few.

Above all, the opportunity to listen directly to young people connects us to communities in better ways, especially when listening and good dialogue go beyond simple box-ticking exercises. For that reason, all major housing projects should involve children and young people as part of the community engagement process.

Designing housing with children and young people in mind doesn’t just benefit them – it enhances the quality of life for the entire community. Spaces designed for play and social interaction create opportunities for people of all ages to connect, while features like traffic-calmed streets and overlooked communal areas promote safety and foster a stronger sense of belonging. When developments prioritise accessibility and inclusivity for children, they naturally become more liveable for everyone, from parents and carers to older residents.

This approach also brings long-term benefits. Developments that are carefully planned with young people’s needs at their core are more likely to encourage active use of shared spaces, build intergenerational connections, and create resilient neighbourhoods. By embedding these principles into housing design, we can move beyond narrowly focused developments and instead deliver places that support vibrant, sustainable, and cohesive communities for generations to come.

> Also read: Creating places and spaces where children and young people thrive

Postscript

Dinah Bornat is co-director of ZCD Architects. Her book, All to Play For: How to design child-friendly housing, is published on 1 February.

No comments yet