John Soane had a lot on his hands but with the built version of a pattern book and accomplished craftsmen he pulled it off, says Gillian Darley

Sometimes, even after a series of catastrophes, a strong, simple building can still reveal its original architectural quality – in unexpected ways. St John’s Bethnal Green has had more than its share of disaster, burnt out in the 1870s and unsympathetically reconstructed, before falling victim to an air raid in 1941.

Logically, there should be almost nothing to point to the hand of its original architect, John Soane. It was one of the 1818 Commissioners’ churches, the so-called Waterloo churches built to mark the end of the Napoleonic wars, among the many dozens built throughout the country to accommodate the hoped-for new congregations in fast-expanding industrialising cities. Soane was responsible for three, all in London, a very reluctant ecclesiastical architect due to the constraints of scrimped budgets and his own distance from establishment religion.

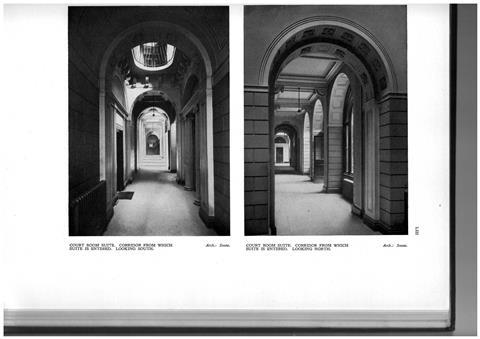

Inside this overlooked Soane work, behind the (open) front door, is a clever and beguiling entrance space, a cross axis linking two (surviving) stairs. It conjures up the long-lost – and considerably more elaborate – series of intersecting lobbies, passages and vestibules which formed connective tissue at the Bank of England, demolished almost a century ago but recorded in FR Yerbury’s photographs.

Despite its current shabby state, at St John’s Soane played to his strengths – making much of in-between places and links. He could pull examples out of his back catalogue, references for his master craftsmen. By this means, he transformed a cut-price, lacklustre commission into something out of the ordinary.

By having a system of established, replicable features he could cope with a rising tide of work in the early years of his career. Telling the plasterer, the stonemason, the bricklayer or the carpenter, “do the entrance at X like the one you did at Y” was enough. The artisan team, many of whom remained at his side over the decades, knew all the favourite details, continually adjusted but essentially always recognisable.

When I wrote my biography of John Soane this understanding and equilibrium between the professional man and the craftsman struck me forcibly, a mutual respect that rarely survives in the contemporary building world. Yet in high-quality architectural conservation the match between skills, the design of the repair or the new work as the case may be, and the materials is, frequently, a seamless affair, driven by shared principles and due recognition of what each participant brings to the job.

Those tell-tale signature passages – in both senses – in Soane’s architecture, whether in his own house on Lincoln’s Inn Fields or at the Bank were the proof of his ingenuity.

They are also testament to that loose team which took him from early obscurity in the 1780s to acclaim in the early decades of the 19th century, from the handling of a passage of plaster moulding to the fine detail of the carpentry. Soane, himself the son of a bricklayer, well understood how dependent he was on their skills and, as a result, irascible to most around him, he always treated his artisans with exemplary fairness.

Not all architects like to be team players, finding it all too easy to overlook the specialists, be they technicians, engineers or landscape designers, on whom they have been highly dependent. But wise heads like Soane know exactly how beholden they are to their colleagues, all the way through until the very end of the job.

No comments yet