Stephane Paumier’s combined French-German embassy in Dhaka expresses in bricks and mortar an international embrace at the heart of the EU, says Ben Flatman

This month the New York Times controversially described Britain as “embracing an introverted irrelevance” in its relations with the rest of the world, provoking nods of agreement from many and howls of indignation from Brexiters. The UK is widely seen as having abandoned its global role.

What’s left of a UK foreign policy appears subordinated to the urgent need for new friends and trade deals to replace access to the single market and the EU’s own 50-odd free trade agreements when it leaves the bloc in 2019. And as Britain struggles with the economic and political fallout from Brexit, the pressure grows on France and especially Germany to fill the UK-shaped hole on the international stage.

One of the EU’s defining features has always been the strength of the Franco-German alliance that lies at its heart. But this closeness has also created tensions and resentments, as well as unity. The UK acted as a counterbalance to this relationship, and as a powerful and effective advocate for the single market, but France and Germany were always the true believers in the political aim of an “ever closer union”.

With Britain almost certainly out of the picture, the two main drivers of the EU project are now seen as free to construct a vision of Europe less restrained by British foot-dragging. But the UK’s departure also creates new challenges and expectations. While embracing Germany closely, the French, and other smaller European nations are also wary of Germany’s dominant economic position. Weighed down by its own history, Germany struggles with its growing influence and the expectation that it take a more assertive role in defining Europe’s foreign and defence policy.

Depending on where you stand on the issues of sovereignty, harmonisation and subsidiarity, the UK’s departure from the EU could either be an opportunity to rejuvenate Europe, or mark the beginning of a potentially dangerous lurch towards an unwieldy and rigid super-state.

Either way, the prevailing view from the rest of the world is that France and particularly Germany are now incontrovertibly Europe’s leading powers. Whether that partnership is strong enough or sufficiently balanced to sustain the pressures and expectations now placed on it will be a key test of whether, and in what future shape, the EU survives.

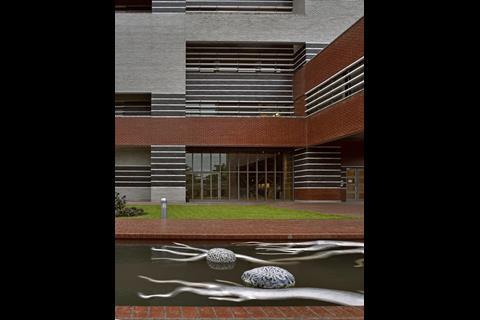

In June this year both countries unveiled a powerful symbol of their shared values and commitment to a unified foreign policy, when they took possession of an almost unique combined embassy building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Designed by the Delhi-based French architect, Stephane Paumier, the building is inspired by DNA’s double helix structure, and literally entwines the French and German embassies around each other, coalescing on a central shared space on each floor. In this diplomatic mission the two countries are now metaphorically and physically tied to each other. As architecture it arguably represents the exact opposite political sentiments to Brexit, Trump and the growing tide of nationalism and isolationism.

Paumier’s work is mainly centred on India and is not easily categorised. His education in France was profoundly influenced by Group UNO and the Peruvian experimental modernist Henri Ciriani. He is drawn to large-scale and complex briefs, and his projects include huge university campuses and corporate HQs. The scale of some of his commissions is not something most medium-size European practices would normally get the chance to work on. Paumier clearly relishes the opportunities presented by South Asia’s exploding mega-cities, with their potential for massive and impactful interventions. He believes “European cities are finished in many ways and need improvement only at the margin” and contrasts this with the urban environment of India, a country whose cities, like those of Bangladesh, he describes as being “in a complete mess”.

One of Paumier’s earliest projects after graduation was the Alliance Francaise in Delhi, out of which he grew his Indian practice. Although he started his career working for the French government, this is his first embassy commission. As an architect, the requirement to design for two government clients made the Dhaka project doubly challenging, reflected in the fact that it took eight years from winning the project in 2009 to opening in 2017. The French acted as lead client, and Paumier somewhat confirms national stereotypes by stating that “the Germans are very concerned that process is followed step by step at any cost, while I would say the French tend to be more focused on how best to reach the destination. A more linear versus a more diagonal thinking process and work culture”.

Paumier sees the new embassy as the built manifestation of the Élysée Treaty, signed in 1963 by Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer. The treaty bound into law the requirement for both countries to work together and consult closely on a wide range of issues, and was reconfirmed during anniversary celebrations in 2003. France and Germany have a number of other shared diplomatic offices in cities including Dubai and Pyongyang, but this is their first purpose-built combined embassy. The sharing of premises also has a more prosaic function, according to Paumier. “It is also an economic consideration where the cost of land in Asia is extremely high. Being alone on your plot does not make sense as the built potential of the plot is often not fully exploited.”

Interestingly, the Élysée Treaty was originally seen as serving quite different ends by France and Germany. De Gaulle wanted to tie Germany to France in order to bolster European independence from the US and keep out what he regarded as its untrustworthy interlocutor, Britain. In the same year as the treaty, De Gaulle vetoed the UK’s entry to the EEC, declaring, “l’Angleterre, ce n’est plus grand chose” (“England is not much anymore”). De Gaulle would no doubt have been pleased by Brexit.

In contrast, the German parliament only ratified the treaty after adding a preamble (under pressure from President Kennedy) that made a commitment to closer cooperation with America and support for eventual British membership of the EEC. These tensions and sometimes divergent visions for Europe have never entirely gone away, with Emmanuel Macron today once again projecting something of a Gaullist sense of French exceptionalism, in marked contrast to Chancellor Merkel’s quieter brand of internationalism.

But today the wider world seems a very different place. The framework on which the US built its foreign policy since the Second World War is being dismantled before our eyes. One thing hasn’t changed however. Just as Britain faced a post-imperial identity crisis in the 1960s, so this month’s New York Times article highlighted that once again “no one knows what Britain is anymore”. Henry Kissinger supposedly once asked: “Who do I call if I want to speak to Europe?” Brexit has made one thing clear: increasingly detached and parochial, no one is going to be calling the UK.

The new Dhaka embassy building, conceived long before Brexit, now feels as if it represents the profound importance of Franco-German relations to the future of Europe, and the hopes placed upon that alliance. In brick and concrete it tells a story of historic reconciliation and cooperation constructed from the aftermath of a catastrophic war.

With Britain widely perceived as entering a new period of disengagement from Europe and the wider world, many will be hoping that the enduring relationship between France and Germany is now able to sustain a set of political and cultural values that seem increasingly under threat.

2 Readers' comments