At a conference to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Milton Keynes, David Rudlin finds the future is not what it used to be

The future is certainly nowhere near as exciting as it was 50 years ago when Milton Keynes was designated as a new town to the opening chords of Sgt Pepper, with its central axis, Midsummer Boulevard, aligned to the summer solstice.

A new town conceived as men walked on the moon, as Concord was taking its first flight and as Christiaan Barnard was undertaking the first heart transplant and making it feel like we might all live forever.

David Lock, long-time advocate of Milton Keynes and well-known town planner, reminded us of this context as part of a series of events organised by The Academy of Urbanism and the International New Towns Institute to celebrate Milton Keynes’ first 50 years. Hosted in a specially constructed venue in the heart of Centre:MK, the town’s rather wonderful, listed shopping centre, the three days of events were like a Greek polis debating the city in public as members of said public peered through the open sides of the venue, even popping in to listen for a while on their way to John Lewis or Next.

The idea was to use the history of Milton Keynes as a lens to explore the way that we should plan for today’s equally exciting future. There were presentations from the Future Cities and Transport catapults and much talk of driverless cars and drones, the hyperloop and big data, and how these new technologies will change everything. There was less agreement about what this everything might be, and even less about how cities should respond. As Rory Hyde from the V&A said: “The future will be completely different to today and it will take us all by surprise”.

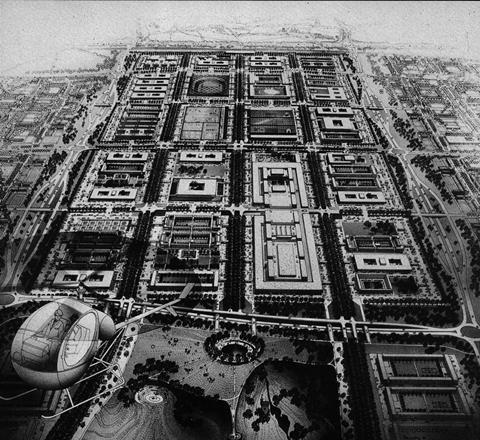

The problem is that a city takes such a long time to build that almost any technology one can imagine will be obsolete by the time it is even half built. Milton Keynes was planned 20 years before the first email was sent, long before mobile phones or the internet. Its lazy grid of one kilometre squares was cast over the Buckinghamshire countryside to create an egalitarian city where everyone and everywhere was equally accessible, provided of course that they had a car, which of course everyone would (if not a personal helicopter like the one in the famous illustration of the city centre by Helmut Jacoby). However as Michelle Provoost of INTI pointed out, it is less egalitarian for the one in five of its households who don’t have a car.

What is depressing, looking at the history of Milton Keynes, is the extent to which we have lost the confidence to plan at all

It became clear from our discussions that our view of the future tends to say more about our current concerns than it does about any objective view of what the future might actually hold. The Future of Suburbia project at MIT concluded that new transport technologies will mean the death of distance and therefore the reinvention of low-density suburbia which, in their view, is much more civilised than elitist cities. The Town and Country Planning Association believes that the same trends means that a new programme of new towns or garden cities is necessary. Urbanists by contrast believe that new technology will reinforce the traditional city, making it more efficient and livable and reinforcing the importance of face-to-face contact. All three are projecting into the future their convictions about the way cities should be. As urbanists we should always be careful to ask whether the dense, loose-fit, mixed-use city that we promote is always the answer to urban problems. It is of course, as David Green from Perkins & Will pointed out, but it’s good to ask.

Just because we can’t predict the future doesn’t mean we can’t influence it. If we plan a city around the private car (with or without a driver) then we shouldn’t be surprised that that is what we get. If we plan a city around smart public transport and walkability then we will end up with something very different.

But this was not the main message to come out of the events in MK. For all the excitement about the future as we presently see it, there were precious few ideas about how cities should respond. What is depressing, looking at the history of Milton Keynes, is the extent to which we have lost the confidence to plan at all. Our current crop of garden cities are small beer compared with the ambition of the original Milton Keynes planners. We may disagree with what they did but we can still admire their ambition and their belief that planning really could change the world.

David Rudlin is chair of The Academy of Urbanism

9 Readers' comments