Herzog and de Meuron’s clumsy proposals for Liverpool Street do not sit easily with the practice’s wider body of work, writes Charles Saumarez Smith

I have been following the plans for the redevelopment of Liverpool Street Station with the utmost interest, partly because I remember, but only just, the last time there was a campaign to save it in the mid-1970s. It was in the early days of campaigning to preserve Victorian heritage, following the recognition of the importance of St. Pancras Station and growing awareness of the need to protect the working buildings and products of Victorian engineering, just as much as the cathedrals and country houses.

The campaign was so successful that the new south entrance which was added in the 1980s was done in a historical style, so much so that people probably don’t realise that it is a modern addition.

When the stations were privatised in the early 1990s, it seems that no provision was made for keeping them up-to-date, so Liverpool Street Station has been allowed to deteriorate. Investment is needed to renovate the historic glass roofing over the railway tracks, there is poor disabled access, and the whole station can feel down-at-heel and overcrowded at rush hour, with a McDonald’s prominently situated next to the main entrance.

So, Network Rail has come up with a plan which has worked well at London Bridge Station, Paddington and King’s Cross – working with a developer, Sellar, who, at London Bridge and Paddington, employed Renzo Piano, to design beautiful new buildings alongside the existing railway station. They used the profits to renew the facilities of the station. I am a great admirer of the Shard and the Cube, both of which are products of a partnership between Network Rail and Sellar.

Instead, someone, perhaps even the architects, came up with a proposal which looks curiously bonkers

The problem is that at Liverpool Street Station, there is no adjacent land to allow any new development, because nearly all the surrounding property was used by Stuart Lipton to create Broadgate in the 1980s. In the last ten years, much of Broadgate has itself been redeveloped for more new offices, including big office developments by Make and Hopkins. Liverpool Street Station is surrounded by office blocks.

One presumes that Renzo Piano was approached for his advice. He may well have said, which is obvious, that there is no available space to do anything adventurous, so James Sellar approached Herzog and de Meuron instead. They were appropriate people to invite to work on the project since they originally made their name with a beautiful new signal box for Basel Railway Station.

At this point, they should have said, as Renzo Piano may have done, that there was not enough space to do much new build, but that they would be more than happy to be involved with an adventurous renovation of the historic railway station. Although the Twentieth Century Society, for good reason, wishes to preserve the 1980s additions, the developers might have been able to persuade the amenity societies that a new addition of the highest architectural quality justified their demolition.

Instead, someone, perhaps even the architects, came up with a proposal which looks curiously bonkers. They decided to airlift a modern office block directly on top of the Victorian Great Eastern Hotel, held up on cantilevered stilts.

Surely, at this point, either Jacques Herzog or Pierre de Meuron should have said that it was an absolutely horrible idea to put a modern building directly on top of a Victorian building without any architectural logic or effectively managed connection: the two buildings do not relate to one another in any way whatsoever. It is a straightforward solecism.

So, the question is being asked, why have Herzog and de Meuron allowed this proposal to go for planning permission? Of course, architectural practices grow in scale and the founding principals may have wanted their London office to choose a big project after their admirably reticent new building for the Royal College of Art.

But as the opening of their celebratory exhibition at the Royal Academy approaches, many people are asking why it is that they have allowed themselves to be co-opted to undertake a project which looks like reputational suicide. They will forever be celebrated as the architects of Tate Modern and the adjacent Blavatnik Building, both of them, in different ways, brilliant projects.

Now, Herzog & de Meuron is at risk of being remembered for putting two tower blocks on top of a Victorian building, which should be a lesson to all architects as to how not to behave.

Coming soon: the case for redevelopment at Liverpool Street

Postscript

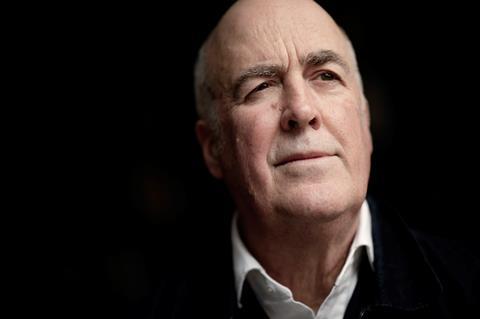

Charles Saumarez Smith is Professor of Architectural History at the Royal Academy, where he was previously both Secretary and Chief Executive from 2007-18. He was also Director of the National Gallery from 2002-07.

7 Readers' comments