Andy Foster reviews Tim Brittain-Catlin’s biography, which sheds light on the life, work, and artistic daring of Edwin Rickards, a key figure in Edwardian Baroque architecture

Sixty years ago, Edwardian Baroque was the style you didn’t mention, especially to architecture students. It was the shocking and disreputable old great-uncle who had been written out of the family history. Pevsner, in the Outline of European Architecture, made one fleeting reference to ‘pompous Edwardian Imperial’. Robert Furneaux Jordan, in his polemical book on Victorian architecture, ignored it completely. When the Pelican ‘A History of English Architecture’, the standard student text for many years, was revised in 1965 to include Victorian and twentieth century architecture, Paul Thompson’s chapter vaulted straight from Barry’s Halifax Town Hall to C.F.A. Voysey. It was a shameful episode, best ignored.

It is still contested history. W.J. Curtis’ ‘Modern Architecture since 1900’, the Holy Bible of history in schools of architecture since its appearance in 1982, can hardly omit Lutyens, but otherwise follows the canon established by Pevsner: the Arts and Crafts; Chicago skyscrapers; the Austrian group, Otto Wagner, Olbrich, Hoffman; Mackintosh; Gropius. Nothing has altered in modernist historiography in nearly a century.

In fact a change in attitudes has been going since the 1970s, though architecture teachers have properly shielded their vulnerable pupils from it. Alistair Service’s compendium, ‘Edwardian Architecture and its Origins’ of 1975 included a section on ‘The Grand Manner’ and his subsequent Thames and Hudson book on Edwardian Architecture had a chapter on ‘High Edwardian Baroque’. David Watkin’s ‘English Architecture’ of 1979 covered the style fully and sympathetically, with its chapter on the twentieth century headed by a full page picture of Deptford Town Hall.

This re-assessment happened in parallel, not accidentally, with that of the work of the first English Baroque, especially Kerry Downes’ books on Hawksmoor; and of the music of Elgar, whose symphonies, dismissed by the mid-twentieth century critic W.J. Turner as ‘Salvation Army’ music, were recorded again by Adrian Boult and John Barbirolli. The architectural revaluation climaxed in Stuart Gray’s 1985 ‘Biographical Dictionary of Edwardian Architecture’ which combined thorough scholarship with an informed judgment of the quality of the buildings involved.

In this re-assessment, one architect, or perhaps practice, stood out: Edwin Rickards, whose partnership with H.V. Lanchester produced only a small number of buildings, but five of them the finest of their kind: Cardiff City Hall, the Hull School of Art, Deptford Town Hall, the Methodist Central Hall in Westminster, and the Third Church of Christ Scientist in Curzon Street, London. They competed for London County Hall and sadly lost; but did design the King Edward VII Memorial statue and fountain in Bristol. Service’s compendium included an excellent, perceptive chapter on Rickards by John Warren. Warren possessed a copy of the memorial volume on Rickards edited by his great friend the novelist Arnold Bennett, with its reproductions of many of his sketches; and he had talked to the Lanchester family. Now, finally, Rickards has had his due, with this excellent biographical study by Tim Brittain-Catlin.

Rickards can stand as the symbolic figure of grand Edwardian architecture and its impact on the society of the period. His lifestyle was what we used to call raffish. He frequented the Cafe Royal. His drawings of female figures suggest intimate knowledge, and Bennett hints at mistresses. He had close male friends in a typical way of the time. Like him, they had made themselves in society from modest backgrounds: as well as Bennett, H.G. Wells. Charles Reilly patronisingly called him ‘little Rickards’. Brittain-Catlin is very good at describing his friendships, and his relations with Lanchester and the extraordinary Lanchester family including H.V.’s brother, the pioneer motor engineer F.W. Lanchester.

What is his work like? Perhaps the best place to start is his sketches. They have an extraordinary quality of line, of verve and dash, once seen, never forgotten. A few perfectly shaped lines and a touch of shading can sketch women dancers, Arnold Bennett huge in greatcoat with matching dog, Baroque fountains, and – more finished but still related – the magnificent tower and colonnade of the proposal for London County Hall. Brittain-Catlin quotes John Summerson: “His sheer, shocking brilliance as a draughtsman is the great thing about him. His buildings positively reek of showmanship… they are the champagne of the period” and when it does fizz, “gosh!” Which strikes me as dead right, as long as you add, as Brittain-Catlin does, that he could use his skill wonderfully to design “three dimensional buildings, created in heavy masonry, sometimes in a combination of stone, concrete and steel”.

It is his quality of line which carries those buildings through. There is a kind of Edwardian architecture, particularly associated with J.J. Joass, though Paul Waterhouse was well capable of using it, which uses the methods of Mannerism to indicate to the informed eye that steel and concrete construction lies underneath traditional facades and spaces, putting elements together in unstructural ways. Rickards does not quite do this, but anyone walking up the staircases of the Methodist Central Hall, with their vastly wide arches, will become aware that they depend on that kind of construction underneath. Yet his design skills take you onwards almost unheeding.

Brittain-Catlin quotes Laurence Weaver’s perceptive comment that Rickards’ “heart was fixed, in the Baroque of Europe” and shrewdly compares his visits there to Vaughan Williams’ contemporary decision to go to Paris to study with Maurice Ravel. Certainly Rickards had an unerring judgment of how to combine structure and decoration. The staircase of Deptford Town Hall is, as Brittain-Catlin says, “one of the most powerful small spaces in English architecture”, but that is partly because its overwhelming, opulent decoration is kept in check – only just, but it is – by a firm architectural framework of arches, columns and cornices.

The work most closely linked to his sketching technique is the King Edward VII Memorial statue and fountain in Bristol, with its flowing, tumbling figures closely related to the ‘New Sculpture’ movement of Alfred Gilbert, Gilbert Bayes, Hamo Thornycroft, and John Cassidy. But his greatest work of all is Cardiff City Hall and Law Courts, a complex worthy of, and partly seen as, a national capitol. How wise Wales would have been to have made it exactly that, instead of Richard Rogers’ rather gimmicky and now dated building, which has spawned some deplorable imitations.

Lanchester and Rickards’ few major completed works show how fleeting the High Edwardian Baroque moment was, before it subsided into Wren-influenced Baroque Classicism. It scarcely reached Manchester, and never Birmingham, which went straight into the Neo-Wren of the Council House Extension. Yet the Black Country has J.G.S. Gibson’s Walsall Council House of 1902. Brittain-Catlin is a bit patronising towards Gibson, “a serial competition winner”, and hints at him pirating Rickards’ designs. That’s sad, because at his best he was almost Rickards’ equal as a spatial designer, as anyone who has climbed the wonderful sequence of Walsall’s staircase will know. And he as much as Rickards must have inspired that excellent building by a local man, George Wenyon’s Dudley library, with its Michelangelesque porch and its staircase with a whiff of the Laurenziana.

It is difficult to see how Rickards might have reacted to the cooler classicism of the twenties. He died in 1920, partly due to overstrain during the war, doing clerical work in France for the War Office. There were big obituaries and the memorial volume edited by Bennett, which may surprise people now.

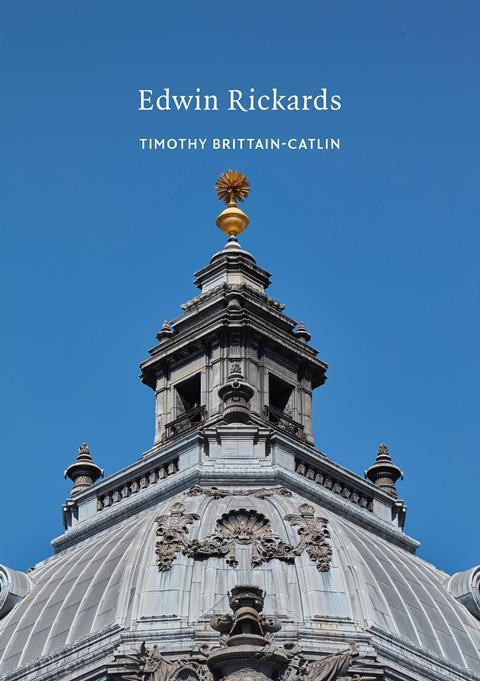

In the last few years, Edwardian Baroque and the ‘New Sculpture’ have again become contested history. G.A. Bremner has claimed the style as both imperialist and sexist. In 2020 John Cassidy’s Edward Colston, the loveliest statue in all Bristol, with its unforgettable, slightly hunched, pondering figure, and its very Rickards-ian pedestal with wriggling dolphins at the corners, was torn apart by a highly-educated philistine mob. In 2021, as Brittain-Catlin records in his introduction, the same wave of agitation saw red paint thrown over the statues on the front of Deptford Town Hall. So this is, in one sense, quite a courageous book. It is also a superb tribute to a great architect. And it has fine new photography by Robin Forster. Buy it, read it. Wallow. Enjoy.

>> Also read: ‘Where sculpture and building come together’: a history of collaboration between sculptors and architects

Postscript

Edwin Rickards by Timothy Brittain-Catlin is published by Liverpool University Press.

Andy Foster is an architectural historian and author of the Birmingham Pevsner City Guide and the Pevsner Buildings of England architectural guide to Birmingham and the Black Country.

No comments yet