The last time the East End land owner tried to bring change to the iconic London thoroughfare, it was met by fierce resistance. With even more ambitious plans now lodged with the council, what are the odds of them winning the locals over? Alex Funk went to find out

When, in the course of your work as a journalist in the built environment, you are invited to poke your nose around a development site, it is usually because someone, somewhere, feels they have something to show off.

Perhaps it is a contractor, showing off the swift and efficient progress of works on the project, or an architect flaunting the glitzy finished product. It could even be the client, proudly exhibiting the building in use.

It is less common, however, to be invited to a site before construction has started, and rarer still to look around a scheme before a planning submission has been made. But it was in this unusual situation that Building found itself earlier this summer at the Truman Brewery in east London’s iconic Brick Lane neighbourhood.

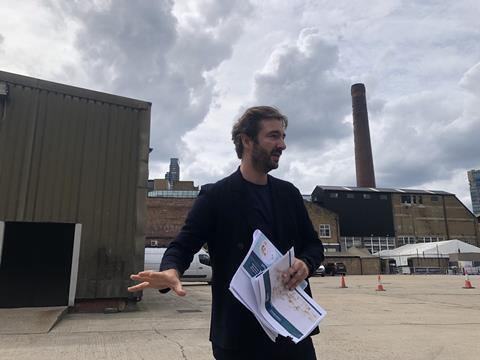

Utilising more imagination than is usually required, Building’s reporter was shown around a network of undeveloped yards and commercial lots just off the famous street by developer Grow Places and masterplan architect Buckley Gray Yeoman.

The battle between Truman and its local opponents is still rumbling on through the courts, but that has not stopped the developer bringing forward even more ambitious plans

The eagerness to provide a steer on media opinion of the scheme may have something to do with the controversy that was sparked in 2021 when Truman brought forward the proposed first phase of redevelopment of its site. Local opposition to that scheme gave birth to the Save Brick Lane coalition, which brought the development to a halt.

The battle between Truman and its local opponents is still rumbling on through the courts, but that has not stopped the developer bringing forward even more ambitious plans for a second phase, begging the question: What do they think will be different this time?

Once one of the largest breweries in the world, the site was bought and transformed by the Zeloof family in 1995 after its doors shut in 1989 due to financial strain. In February 2020, the owners of the Truman Estate proposed a large-scale development that ignited a battle between developers and the local community.

The proposal involved the commercial regeneration of three plots of land, amounting to one acre, which would be used to facilitate buildings ranging between two and five storeys containing retail units, office space and other amenities.

A storm of opposition to the proposed development rolled in, in the form of protests, over 7,000 objection letters and the formation of the Save Brick Lane coalition.

While council members thought the proposal did not serve the community’s needs, small traders felt the threat of large retailers and heritage groups sought to protect Brick Lane’s assets.

It is not difficult to see why the area’s supporters feel so strongly about retaining its distinct character. From one of London’s best independent book shops to the bagel takeaway that never shuts, there is not an appetite that cannot be served on Brick Lane. But, beneath the piles of vintage clothing and crafts stalls, lies the beating heart of the nation’s Bangladeshi community.

Running from Bethnal Green to Spitalfields, Brick Lane is a collage of centuries of east London’s history. It has become known as “Banglatown” owing to a wave of migration during the second half of the 1900s.

Not only is Banglatown home to 60% of the UK’s Bangladeshi population, but it is also a hive of cosmopolitan life, with the Truman Brewery site hosting food trucks and an eclectic variety of creative businesses.

Perhaps most concerning was the idea of new luxury apartments turbocharging soaring rent prices and pushing vulnerable people out of their homes.

In September 2021, the council approved the contentious plans by a two to one vote with a fourth councillor being blocked from voting. Although unable to attend the meeting in person, she said that she would have voted against the development to prevent it from being passed.

The ugliness somehow becomes a part of what makes the space beautiful

Amr Assaad, director at BGY

The Save Brick Lane coalition launched a court case against Tower Hamlets, arguing that it was unlawful for the council to restrict her vote, which collected £21,687 in crowdfunding. The case reached the Supreme Court and is currently awaiting a verdict after the hearing was held on 25 July.

Undeterred, Truman has ploughed on with a second set of proposals, separate from – rather than replacing – the first, which involve a far more drastic re-imagining of Brick Lane. Buckley Gray Yeoman was the architect on board for the original plan and resumes its role as masterplan architect.

According to Amr Assaad, director at the practice, the project team is following a three-step approach to tackling the regeneration. This includes making the best of “unloved gems”, such as the old Cooperage, which used to produce barrels for the Truman Brewery; finding ways to entice people into the area; and repurposing less valuable structures in a way that is “sustainable and contextual”.

“We really embrace the industrial nature fully,” says Assaad. “The ugliness somehow becomes a part of what makes the space beautiful.”

Developer Grow Places was not involved in the previous project and was appointed to the current endeavour in spring last year. Tom Larsson, founder of the young company, describes how the “ethos and principles” of the project were handed down from the owner, who he says is “eager to regain control and stewardship”.

“What Truman and ourselves have been doing in terms of the brief is not necessarily the usual way that the architectural industry would operate. We need to make space that isn’t about the architecture, it’s about what happens,” explains Larsson.

Pacing through the future building site, taking in the plain of ground and brick, the regeneration team emphasised that this is exactly what we were brought here to see.

“These blank brick walls don’t necessarily hold a great deal of architectural merit, but they are so important to the character and spirit of Brick Lane and we want to provide more opportunities for that,” Larsson tells us.

Standing on the edge of Allen Gardens, facing walls which are currently nothing more than a canvas for graffiti tags reminding everyone who Brick Lane really belongs to, Assaad chimes in: “I can’t think of any other client where their brief is: ‘This building has to have graffiti on it, this building has to be robust, it can’t be too showy’.”

The new design features redevelopment across eight blocks on the site for various uses, such as retail and market space, event/exhibition space, offices and greenery. There would also be 44 new homes, including “affordable housing”.

It’s a big piece of land and a neighbourhood that people love and care about deeply and therefore it should have scrutiny, and we welcome that scrutiny

Tom Larsson, Grow Places founder

Larsson acknowledges the controversy around the previous scheme and speaks about its tailored plan to address the needs of the community.

“It’s a big piece of land and a neighbourhood that people love and care about deeply and therefore it should have scrutiny – and we welcome that scrutiny, because it’s all part of the process. No one scheme is ever going to meet everyone’s aspirations,” he says.

He notes the sense of communal anxiety that seems to pollute the area, inspiring a fierce resistance to change, which he claims will be remedied by “talking to people” and “engaging with public entity data”.

He explains: “For the consultation events, we’ve notified 11,000 local residents within quite a big radius around here. All of the invites, boards and any pamphlets have been presented in English but also in Sylheti, which is the predominant dialect for the Bangladeshi British community who are in this area.

“We’ve also had an interpreter on site at the events, so we’ve tried to be as inclusive as we can. We’ve held events in different locations, some in the local community centres and some online as well.”

Grow Places’ strategy seeks to retain the spirit of the area, but how plausible is this goal when entire buildings will be demolished and huge commercial structures erected in their place?

Larsson clarifies: “The success at this point is if you don’t necessarily feel where the old brewery started, or where the new scheme begins, but even more so than that, you don’t feel where Truman Brewery starts and ends – it just feels like part of Brick Lane.”

The success at this point is if you don’t necessarily feel where the old brewery started, or where the new scheme begins… it just feels like a part of Brick Lane

Tom Larsson

The team seem confident in their public consultation methods. “I think people appreciate the process that we’re going through and the fact that we had three very involved consultation events running for four to five days each one,” Larsson says.

When asked specifically about pushback from the coalition, he does not seem phased, confirming that they had addressed the needs of their opponents. “The big thing [on their website] was about opening up the site, finding new routes and connections through it.”

The Banglatown Cash & Carry was identified as being of high importance to locals and will therefore be temporarily relocated while the zone is being developed but will return to its original position post-construction.

It is clear that the team have done their homework, with their vision involving the area’s current demographic enjoying the new amenities as well as attracting new visitors.

“Tower Hamlets, particularly this ward, is at the highest level of social deprivation. Also, it’s got a very young population, particularly within the estates to the east,” Larsson acknowledges.

The site is not currently accessible from the east, so plans specify opening the site up to invite the community in, aiming to create a sense of cohesion within Tower Hamlets’ diverse but unequal population.

New scheme in detail

The proposals centre around the regeneration of over 1.3 hectares of the estate, with six new buildings and upgrades to two existing ones across eight blocks.

The boiler house building, recognisable by its ‘Truman’ chimney would undergo a three-storey extension to host exhibitions and events.

Behind the boiler house on Buxton street, a large seven-storey data centre would replace the existing ancillary buildings, designed by Morris + Company with retail, cafe, cinema and community uses on the lower floors. Meanwhile, offices on the upper storeys would be connected by bridges. The new venue would replace a blank wall along Buxton street, creating a wide pavement opposite Allen Gardens, where pedestrian access is currently lacking.

Spital Street’s two-storey historic Cooperage building would continue as a creative workspace, with the additions of a new micro-brewery and an art gallery, designed by Carmody Groarke.

Neighbouring the cooperage sits the estate’s single storage waste facility, which would be relocated to make way for a three-storey creative workspace with two small retail units and a cafe at ground floor.

The site’s existing ‘Backyard Market’ would be dismantled to become a seven-storey building designed by Buckley Gray Yeoman, hosting retail, market and restaurants at ground floor level and offices above.

Across the road, the warehouse currently let to Banglatown Cash and Carry would be turned into a seven-storey housing complex by Henley Halebrown, including affordable and family homes, workspace, retail and a replacement supermarket. A private residential courtyard, cycle stores and blue-badge parking bays will also feature.

On Brick Lane’s western side stands an abandoned building to be redeveloped by Morris + Company into a four-storey data centre with biodiverse roofs. Meanwhile, another new venue will take up Ely’s yard, featuring a food hall on the ground floor to serve the office workers above.

Following the site tour, Building’s reporter took another stroll down Brick Lane, only this time to speak to local businesses about their views on the huge development in the works. However, she found herself telling traders about the proposal on their doorstep, rather than the other way around.

It soon became clear that, generally speaking, a lot of people had not caught the most recent episode of this Truman show.

On our quest for meaningful and informed commentary, workers offered up looks of confusion, references to the proposals from around four years ago and sheepish admissions that they had never heard of the Save Brick Lane coalition.

When all that remained of our reporter’s iced latte was rapidly melting ice cubes, she finally stumbled upon someone with a story. After four years of trading in the Truman Brewery clothing market, a vintage fashion business owner moved his operation to a nearby Brick Lane venue at the start of 2023.

His accountant had advised the move, noting “the pattern of [Truman Brewery’s] behaviour of selling [property] off.”

London is changing and we have to accept it

Jakub, food truck owner

He tells us that the Truman Brewery operation has a “really aggressive nature” of pushing out small businesses. He claims that “huge conglomerates” threaten the livelihoods of independent companies, who struggle to compete for rental spaces. He also expresses a widespread criticism of the new development – the “danger of Brick Lane losing its charm”.

Despite such views circulating among some traders in the area, Larsson paints a different picture. “They are not looking to sell out,” he says of the Truman Brewery owners. On the contrary, those involved in the project see it as an “evolution rather than a revolution”.

Grow Places’ Larsson describes the decision to develop the vast site “incrementally” as a “credit” to Truman Brewery, citing the buildings left derelict for 30 years behind Ely’s Yard as evidence. Ely’s Yard, named after the Zeloof patriarch who bought the site in 1995, currently plays host to a handful of food trucks and a bar.

Jakub, the owner of one of the food trucks, has a more positive attitude towards the impending change. “I think it’s a good thing,” he says. “London is changing and we have to accept it.”

He welcomes the increased footfall, noting that Ely’s Yard has been quiet since the covid-19 pandemic and that paying a higher rent price would be worth it if the business thrives.

East End Trades Guild (EETG), a heritage group who feature prominently in the Save Brick Lane coalition, disagrees. “We want the needs of the local community for genuinely affordable homes and workspaces to be prioritised in the redevelopment of the Truman Brewery,” says Krissie Nicolson, director of the group.

We reject this soulless corporate-style development that will push up rents on Brick Lane, driving out the small independents and undermining the long-established Bangladeshi community

Krissie Nicolson, director of EETG

“We reject this soulless corporate-style development that will push up rents on Brick Lane, driving out the small independents and undermining the long-established Bangladeshi community.

“The development does not factor in the needs of the local communities, who have been vocal about the lack of housing, community facilities, parks and doctors’ surgeries.

“We want to see the site used for building more social housing units run by the council to cater to the demand, as the council has a long waiting list. Brick Lane, much like other parts of London, does not need its character changed with empty glass buildings with office spaces.

“If there is one lesson we have learnt from the pandemic, it is that office spaces are now futile, which begs the question: who is this development really for then?”

Despite the efforts of Grow Places to bring the community in, it appears that what little local opinion currently exists about the proposals is still cut through with scepticism and distrust.

The courts will decide the fate of Truman’s first set of redevelopment plans. As for its second attempt, it seems that the project team has another battle on its hands.

Additional reporting by Daniel Gayne

No comments yet